by Carl A. Volz

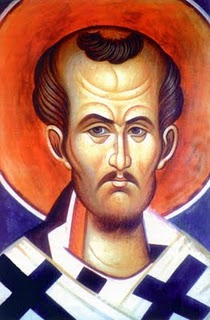

John Chrysostom loved to preach.

John Chrysostom loved to preach.

“Preaching improves me,”

he once told his congregation.

“When I begin to speak, weariness disappears; when I begin to teach, fatigue too disappears. Thus neither sickness itself nor indeed any other obstacle is able to separate me from your love.… For just as you are hungry to listen to me, so too I am hungry to preach to you.”

And people loved to hear him preach, and since his death, to read his sermons. He was given the posthumous title of “Chrysostom” or “golden tongue,” and it stuck. Pope Pius X in 1908 designated him as the “patron” of Christian preachers. And historian Hans von Campenhausen wrote that his sermons

“are probably the only ones from the whole of Greek antiquity which … are still readable today as Christian sermons. They reflect something of the authentic life of the New Testament, just because they are so ethical, so simple, and so clear-headed.”

What was it like to hear a Chrysostom sermon? What was it about his method, style, and content that established his reputation as one of the church’s greatest preachers?

Standing Room Only

John preached every Sunday and saint’s day in addition to conducting several weekday services, which accounts for the 800 sermons still available to us today. He began his sermons with a prayer that many Christians still pray each Sunday:

“Almighty God, unto whom all hearts are open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid; cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of your Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love you, and worthily magnify your holy name, through Christ, our Lord.”

In the fourth century—indeed, until modern times—people did not sit in pews when they worshiped. Instead they stood or walked around, greeting people and exchanging news. It was to such a relatively unruly congregation that Chrysostom preached, and the people often responded with applause, or on occasion, with boos, hisses, or silence.

Chrysostom once observed that Christ did not have to contend with such ill-disciplined hearers, but the disciples always waited quietly and politely until he had finished. So John concluded his sermon by suggesting that all applause should henceforth be forbidden—and this announcement brought down the house with applause!

Though some of Chrysostom’s sermons lasted more than two hours, other sermons (such as each of his 88 homilies on the Gospel of John) took less than thirty minutes to deliver.

In one of these sermons, we gain a glimpse of church life in John’s day. Just before he gave the Gospel reading, he exhorted his people,

“Each of you take in hand that part of the Gospels which is to be read in your presence on the first day of the week. Sit down at home and read it through; consider often and carefully its content, and examine all its parts well, noting what is clear and what is confusing. From such zeal there will be no small benefit to you and to me.”

This suggests that his listeners were literate and possessed copies of the Gospels.

Sober Exposition

Though Chrysostom’s delivery was dramatic, his biblical exposition was sober and restrained. He was the primary representative of “Antiochene exegesis,” a method that emphasized the literal meaning of the Bible’s text. This school opposed allegorical interpretations of the Bible, which were typical of the church in Alexandria. Allegorists, like the great Origen, went beyond the literal text to uncover spiritual meanings behind the numbers, colors, characters, and events of Scripture—sometimes to the point of becoming rather fanciful.

Chrysostom combated any interpretation of Scripture that didn’t take the literal meaning of the text seriously. Once, in attacking Gnosticism, a heresy that minimized the importance of the physical creation, he wrote,

“Nowhere in Scripture do we find any mention of an earth which is merely figurative.”

His sermon on the healing of the paralytic is a good example of John’s biblical exposition.

Exhilarating Style

John delivered his sermons with all the oratorical skills he had learned from the great Libanius. Sometime before he was ordained, John wrote a book, On the Priesthood, in which he devoted two chapters to the art of preaching. In those, he reminds would-be preachers of

“the great toil which is expended upon sermons delivered publicly to the congregation.”

Hearers may give them scant credit,

“assuming the role of spectators sitting in judgment.”

The people, he wrote, often come not to be instructed but to be entertained.

“Most people usually listen to a preacher for pleasure, not profit, as though it were a play or a concert.”

Indeed, despite John’s clear love for the people, his expectations were low:

“It generally happens that the greater part of the church consists of ignorant people.… Scarcely one or two present have acquired real discrimination.”

Thus, the preacher must rid himself of the desire for praise yet strive for an eloquence that will gain people’s attention. Eloquence is not given by birth, but the preacher must

“cultivate its force by constant application and exercise.”

Chrysostom seemed to have mastered it: even though some of his sermons lasted two hours, people still called for more.

Prophetic Toughness

Chrysostom preached often against worldliness and the neglect of the poor—preaching that today we call prophetic. For example, in the 90 sermons on the Gospel of Matthew, Chrysostom referred 40 times to almsgiving, 13 times to poverty, more than 30 times to avarice, and almost 20 times to wrongly acquired and wrongly used wealth.

In one sermon he asks the rich,

“You say you have not sinned yourselves. But are you sure you are not benefiting from the previous crimes and thefts of others?”

Later he says,

“When your body is laid in the ground, the memory of your ambition will not be buried with you; for each passerby as he looks at your great house will say, ‘What tears went into the building of that house! How many orphans were left naked by it, how many widows wronged, how many workmen cheated out of their wages?’ Your accusers will pursue you even after you are dead.”

On another occasion he warned,

“I am going to say something terrible, but I must say it: Treat God as you would your slaves. You give them freedom in your will: then free Christ from hunger, want, prison, nakedness!”

Pastoral Tenderness

Because of John’s emphasis on the duty of Christians, some criticized him for being moralistic, even Pelagian (believing that good works lead to salvation).

In fact, Chrysostom preached 32 sermons on Romans that were later used by Augustine to demonstrate that Chrysostom could not be so accused:

“What is it that has saved you?” John preached. “Your hope in God alone, and your having faith in him in regard to what he promised and gave. Beyond this there is nothing that you have contributed.”

In addition, though he was harsh with his people, he always preached with hope.

“Have you sinned?”

he added to one sermon on repentance.

“Go into the church and wipe out your sin. As often as you fall down in the marketplace, you pick yourself up again. So too, as often as you sin, repent of your sin. Do not despair. Even if you sin a second time, repent a second time. Do not by indifference lose hope entirely of the good things prepared.

“Even if you are in extreme old age and have sinned, go in, repent! For here there is a physician’s office, not a courtroom. [The church] is not a place where punishment of sin is exacted, but where the forgiveness of sin is granted. Tell your sin to God alone: ‘Before you alone have I sinned, and I have done what is evil in your sight.’ And your sin will be forgiven you.”

Sometimes after scolding his hearers, he showed them his pastoral intent:

“My reproach of you today is severe, but I beg you to pardon it. It is just that my soul is wounded. I do not speak in this way out of enmity but out of care for you. Therefore I will now strike a gentler tone.… I know that your intentions are good and that you realize your mistakes. The realization of the greatness of one’s sin is the first step on the way to virtue.… You must offer assurance that you will not fall into the same sins again.”

Without Equal

Chrysostom has had his critics, ancient and modern. Socrates, a fifth-century historian, faulted him for

“too great a latitude of speech,”

and modern historian W. H. C. Frend says,

“He was tactless toward colleagues.”

His courage and candor earned him a reputation as a great preacher and faithful Christian. But in his day, his only reward was exile and death. In his final sermon, he seems to have seen what was coming, and he faced it with characteristic courage and style:

“The waters are raging, and the winds are blowing, but I have no fear for I stand firmly upon a rock. What am I to fear? Is it death? Life to me means Christ, and death is gain. Is it exile? The earth and everything it holds belongs to the Lord. Is it loss of property? I brought nothing into this world, and I will bring nothing out of it. I have only contempt for the world and its ways, and I scorn its honors.”

Despite his scorn of honors, such passages cause us to honor him 1,600 years later—as one without equal among the preachers of antiquity.

Carl A. Volz was professor of church history at Luther Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota. He is author of Pastoral Life and Practice of the Early Church (Augsburg/Fortress, 1990)

Reprinted from Christianhistory.net