by Regis Nicoll

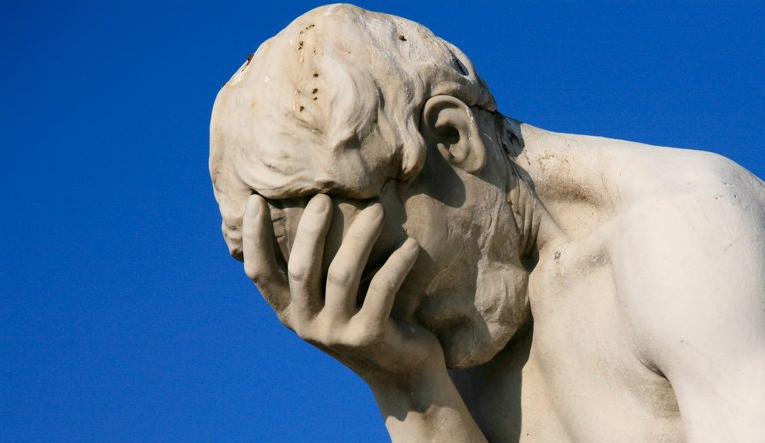

A definition of insanity – doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. Teaching, making disciples – it matters. Will we learn from mistakes?

“A 50-year failed experiment.”

That’s how Scott T. Brown, a once-prominent figure in the youth ministry movement, describes youth ministry.

Is Brown being too negative? Possibly — if our purpose is to corral young people and entertain them in “safe,” Christian environments until they leave home. But if the goal is to grow the next generation of disciples and church leaders, then youth ministry is an experiment that has not only failed, but failed miserably.

Not only are young people de-churching in droves (anywhere between 60 and 85 percent after they turn 18), they are not re-churching after getting married and having children as in previous generations. What’s more, those who remain churched tend to develop less orthodox views about the faith and moral behaviors.

For example, one study found that 70 percent of churched youth have serious doubts about

“what the Bible says about Jesus.”

Another found that 80 percent of evangelical Christians, aged 18 to 29, have had premarital sex. Many of these are young adults who were nurtured in age-appropriate ministries from the time they were in Huggies.

Today, Sunday School classes are equipped with state-of the-art multimedia that would have had little more than hand puppets and a felt board a generation ago. At a megachurch I visited a few years back, entering a children’s classroom was like stepping into a Disney World attraction. Classes were decorated around themes like “Pirates of the Caribbean,” “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” and the Starship Enterprise, with no expense spared.

Churches have built youth centers, hired youth ministers, developed youth programs, provided youth activities, sponsored youth camps, and offered worship services for youth by youth, all the while youth stream out of their doors in record numbers, leaving parents and church leaders to scratch their heads wondering why and what’s to be done.

Something’s missing

David Kinnaman of the Barna Group says that one of the top reasons young Christians leave church is the shallowness of faith they experience there. From a five-year study on the youth exodus, Kinnaman reports that 20 percent of young adults who were active in church during their teens said that God seemed missing from their church. Matt Chambers, a 30-something preacher’s son, would agree.

Beginning around the age of eleven, Matt writes,

“I would read about Jesus, and how he treated people, then I’d look at Christians, and the two just didn’t match up.”

Matt goes on to say,

Sometimes we’d go by the church to surprise my dad in the middle of a work day, and there’d be someone in his office yelling at him for changing the carpet, or not using the choir robes. We would receive threatening anonymous letters at our house . . . certain church members would interrupt the service to call meetings. They wanted to edit sermon content. They hated the music. They controlled the finances. They cursed. They slandered. They schemed.

Not wanting to

“end up looking like those people,” Matt said “[he] washed [his] hands of the church.”

And who can blame him? When people in church are not noticeably different from those outside of church, is it any wonder young adults sense that something, or Someone, is missing from church?

Don’t ask, don’t tell

Then there’s Rigoberto Perez, a 30-something former Seventh-day Adventist. Rigoberto told NPR that church

“was a fairly important part of our lives. It was something we did every Saturday morning.”

Rigoberto went on to tell of an alcoholic father, a suicidal brother, and dysfunctional home marked by abuse and instability. And that prompts an unsettling question: Where was the church in the life of this churchgoing family?

The answer suggested is even more unsettling: The church was uninvolved — either because it didn’t care or, more likely, because it was content with transmitting information and assuming that if we don’t ask, and they don’t tell, all is well.

One bit of information transmitted to Rigoberto was the belief that personal hardships are given to “try” us. But after losing his mother to cancer and his brother to suicide, on top of the lifetime of the hardships he had already been “given,” Rigoberto concluded that was

“just too hard to believe anymore.”

And that points to another reason young Christians leave the church: They feel that it is an unwelcome place to express doubts and ask hard questions. Too often doubts are waved off with a stern warning to doubters about the dangers of doubting, and hard questions are trivialized or given such short shrift as to be unhelpful to someone being squeezed in a pressure point of life.

Costly consequences

Rigoberto’s experience — one that is more common than we want to admit — is a bracing reminder of the cost of non-discipleship. When churches fail to disciple their members, the consequences are more serious than falling attendance and shrinking budgets.

Until the church becomes a place where people are nurtured into a ferrous faith and are comfortable with sharing serious life questions, young people like Rigoberto will continue turning elsewhere for answers. I think I mentioned the high percentage of Christian kids who have serious doubts about the faith and the higher percentage admitting to unbiblical behavior.

But the hard reality is that we can’t pass on what we don’t have. The yawning (and well-documented) gap between profession and practice among Christians bespeaks a faith that is more flaccid than ferrous.

Adults and, especially, parents whose Christianity is religious gloss rather than spiritual substance cannot lead children to a deep, muscular faith. And without that, no amount of pandering to youth with youth worship services, rock music, campouts, and Friday night volleyball with pizza and Coke will hold them in the church orbit. The only thing capable of exerting a lasting pull is the Good News authenticated in the lives of those who profess it.

The faith young people see must line up with the faith they hear — if not, they will turn their ears from it. But to see the faith, young people need to be integrated into a church that exemplifies the faith; and that means change — big change — for churches where optional discipleship and generational division are the norm.

Integration

It’s Scott Brown’s opinion that the common practice of segregating services and classes by age has led to church attrition rather than multiplication.

Brown, it should be mentioned, is a leader of the Family Integrated Church movement — an organization that has prompted warranted criticism for some of its more extreme views on generational integration in the church.

Yet to the degree that churches have created sub-cultures isolated from each other, Brown has a point when he suggests that it has served neither the church nor its youth particularly well. Alvin Reed, a professor of evangelism and student ministry, explains,

The generation of teens today is not only the largest, it is also the most fatherless. We must connect students to the larger church and not function as a parachurch ministry within a church building. Students need older believers in their lives. We need a Titus 2 revolution where older men teach younger guys and older women teach younger ladies.

At the same time, it is essential for parents — not pastors, youth ministers, or Sunday School superintendents — to accept the primary responsibility of discipling the next generation.

In Deuteronomy, God instructs the Israelites to

“teach [my commandments] to your children and to their children after them,”

then tells parents how to go about it:

Talk about them when you sit at home and when you walk along the road, when you lie down and when you get up. Tie them as symbols on your hands and bind them on your foreheads. Write them on the door-frames of your houses and on your gates.

In his letter to the Ephesians, Paul calls upon fathers to rear their children “in the training and instruction of the Lord.”

To that end, the role of the church is to stir fathers and mothers to the high calling of parenthood and disciple them so that they can disciple their children in a faith that will hold them in a gravitational spiral centered on Jesus Christ.