by Fr. John A. Peck

Part Two of our Five Part series.

A Short History of the Liturgical Location for Preaching: The Ambo, the Pulpit and the Lectern.

The Ambo

An Ambo (pl. Ambones) is a Greek word, supposed to signify a mountain or elevation.

This was understood in the west as well – and well after the Great Schism. Even Pope Innocent III of Rome so understood it, for in his work on the Liturgy (II.I. 33), after speaking of the deacon ascending the ambo to read the Gospel, he quotes the following from Isaiah (40:9):

“O thou that tellest good tidings to Zion, get thee up into a high mountain! O thou that tellest good tidings to Jerusalem, lift up thy voice with strength, be not afraid; say unto the cities of Judah, ‘Behold your God’”

(translation as quoted in Handel’s Messiah – a personal favorite)

And in the same connection he also alludes to Our Lord Jesus Christ preaching from a mountain:

“He went up into a mountain -and opening his mouth he taught them” (Matt. 5: 1, 2).

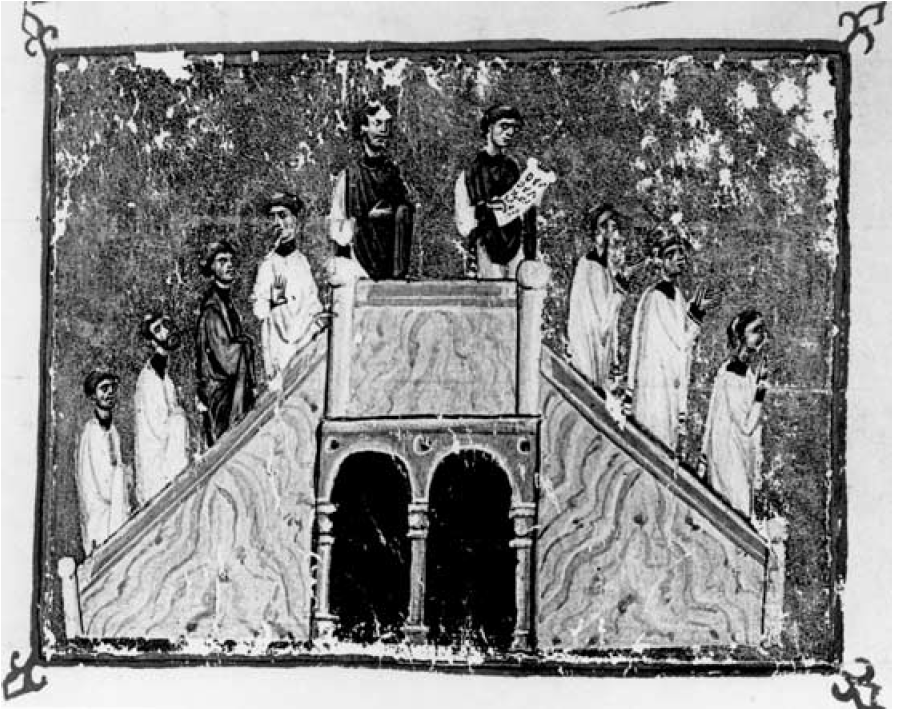

As an ambo is an elevated platform or pulpit from which, in the early churches and basilicas, the Gospel and Epistle were eventuallychanted or read from it, and all kinds of communications were made to the congregation, sometimes the bishop preached from it, as in the case of St. John Chrysostom, who, Socrates Scholasticus says, was accustomed to mount the ambo to address the people, in order to be more distinctly heard (Eccl. Hist., 6, 5). Sozomen (Church History 9.2) states the same, still characterizing the ambo as bema ton anagnoston. Chrysostom spoke from the ambo

“in order to be better understood”;

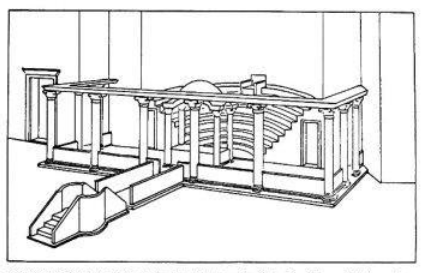

Originally there was only one ambo in a church, placed in the nave, and provided with two flights of steps; one from the east, the side towards the altar; and the other from the west.

From the eastern steps the subdeacon, with his face to the altar, read the Epistles; and from the western steps the deacon, facing the people, read the Gospels. The inconvenience of having one ambo soon became manifest, and in consequence in many churches two ambones were erected. When there were two, they were usually placed one on each side of the choir, which was separated from the nave and aisles by a low wall. Very often the Gospel ambo was provided with a permanent candlestick; the one attached to the ambo in St. Clement’s in Rome is a marble spiral column, richly decorated with mosaic, and terminated by a capital twelve feet from the floor.

In the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia it stood under the dome (Paul the Silentiary, P.G., 86, 2259), but was united with the choir

“like an island with the mainland.”

Similarly at Ravenna the ambo of Bishop Agnellus (sixth century) stood in the central aisle of the nave, on the inner side of the old chancel screen. Bishop Agnellus, builder of the ambo of the cathedral at Ravenna (sixth century), called it pyrgus, or tower-like structure. The exterior surface of the round middle part and the steps which come far forward on the sides have panels arranged like a chess-board in six parallel bands filled with symbolic animals: fish, ducks, doves, deer, peacocks, and lambs in regular succession.

Owing to the aversion of Byzantine art of that period to delineating the human figure, animals are here presented in symbolical dependence on the words:

“Preach the Gospel to every creature.”

In large churches, therefore, the bishops, e.g. Ambrose, Augustine, and Paulinus of Nola, preached from the ambo at a very early date.

The ambo of Salonica, traditionally called “Paul’s pulpit,” appears to be the oldest remaining monument of this kind (fourth to sixth century). It is circular in form, about four meters in circumference, with two stairways, for ascending and descending, and is ornamented with carvings of the three Magi set in niches representing a shell; two ornamental bands are carried around above the niches (“Archives des missions scientifiques,” III, 1876).

Ambones are believed by some to have taken their origin from the raised platform from which the Jewish rabbis read the Scriptures to the people, and they were first introduced into churches during the fourth century, were in universal use by the ninth, reaching their full development and artistic beauty in the twelfth, and then gradually fell out of use, until in the fourteenth century, after the fall of Constantinople, when they were largely superseded by pulpits. In the Ambrosian Rite, the Gospel is still read from the ambo. They were usually built of white marble, enriched with carvings, inlays of colored marbles, and glass mosaics.

The most celebrated ambo was the one erected by the Emperor Justinian in the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia at Constantinople, which is fully described by the contemporary poet, Paulus Silentiarius in his work peri ktismaton. He describes the body of the ambo as made of various precious metals, inlaid with ivory, overlaid with plates of silver, and further enriched with gildings and bronze. The ambo of Hagia Sophia was adorned with flowers and trees. The disappearance of this magnificent example of Christian art is involved in some obscurity. It was probably intact down to the time of the taking of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1203, when it was stripped of its beauty and wealth.

In St. Mark’s, at Venice, there is a very peculiar ambo, of two stories; from the lower one was read the Epistle, and from the upper one the Gospel. This form was copied at a later date in what are known as “double-decker” pulpits. Very interesting examples may be seen in many of the Italian basilicas; in Ravenna there are a number from the sixth century.

Just when it became customary to use the ambo mainly for the sermon, which gave it a new importance and affected its position, is not known.

Isidore of Seville first employed the word pulpit (Etym., XVI, iv), then “‘tribunal,” because from this the priest gave the “precepts for the conduct of life,” proclaiming law and justice.

Isidore also derives “analogium” from logos, as

“the addresses were given”

from it. Thus the ambo became the regular place for the preacher, and its situation was dependent on local conditions.

The Small Ambo

Due to the reduction in importance of preaching, the ambo eventually became smaller in size, and lower in stature, until it slowly began to turn into the pulpit (if attached to a pillar or some other part of the nave) or a large lectern (if unattached). A good example of this is the Ambo in Cluj, Romania. (below)

The Episcopal Ambo

In the contemporary celebration, the last public prayer of the Divine Liturgy is the “Prayer Before the Ambo”. Originally, it was a prayer of thanksgiving said as the clergy descended the ambo at the end of the service. In ancient times, there was a large collection of Prayers Before the Ambo, written for the different feast days of the church year and for those occasional services, such as weddings and funerals, that called for celebration of the Divine Liturgy.

There is also a low platform in the center of the nave called the episcopal ambo where the bishop is vested prior to the Divine Liturgy and where he is enthroned until the Little Entrance. If the bishop is serving in a simple parish church, an episcopal ambo is set temporarily in place. In parishes where this is permanent, when the bishop is not present, an analogion with an icon is usually placed upon it.

Compiled from various sources.