by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

Although the Apostle Peter enthusiastically confessed the identity of Jesus, he was much slower in accepting the message of the Cross. In fact, when Jesus first spoke of his coming Passion, Peter’s immediate response was,

Although the Apostle Peter enthusiastically confessed the identity of Jesus, he was much slower in accepting the message of the Cross. In fact, when Jesus first spoke of his coming Passion, Peter’s immediate response was,

“Far be it from you, Lord; this shall not happen to you!”

So Jesus, having declared Peter “blessed” for his profession of faith, was obliged—within the span of just a few verses—to tell him,

“Get behind me, Satan! You are an offense to me, for you are not mindful of the things of God, but the things of men” (Matthew 16:16-23).

How did Peter accept this reproof? The gospels do not inform us, in so many words, but a later story indicates that the Apostle did not take it very well. At least, the message seems not to have “sunk in.” Let me elaborate:

Everyone knows that Peter, during Jesus’ trial before the Sanhedrin, denied even knowing him. According to the Gospel records, Peter made this denial three times. I want to suggest, however, that Peter, earlier that same night, had already denied what Jesus stood for. Before explicitly denying Jesus, Peter had already repudiated the message of the Cross.

The episode I have in mind was described by Matthew:

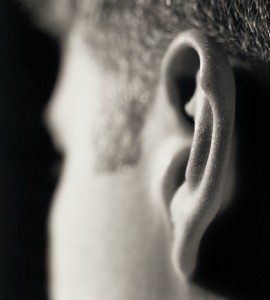

“And suddenly, one of those who were with Jesus stretched out his hand and drew his sword, struck the servant of the high priest, and cut off his ear” (Matthew 26:51).

This incident at the time of Jesus’ arrest was strong evidence that Peter was still

“not mindful of the things of God, but the things of men.”

Moreover, the story of the severed ear conveys an ironic symbolism: Bearing in mind that

“faith comes by hearing” (Romans 10:17),

we are perhaps justified in understanding the man’s loss of an ear as a sort of impediment to faith. Peter amputated the very organ through which a human being normally has access to the Gospel. That is to say, Peter’s assumption of the sword that night, which effectively repudiated the message of the Cross, had the effect of impeding faith.

Peter’s task, as an Apostle, was to bring people to faith, but it was quite impossible for him to do that if he behaved in a way that restricted access to Christ. Thus, when he swung that sword at the high priest’s servant, Peter effectively renounced the ministry for which Christ had chosen him.

Comparing Peter’s action in this scene with his later denial of Jesus in the high priest’s courtyard, I am disposed to believe the former sin worse than the latter. After all, when Peter denied Jesus to the servant maid and others, he was acting in weakness; he was afraid. When however, he swung that sword at the head of the high priest’s servant, he was acting in arrogance, pride, coercion, and recourse to worldly power. He intended harm!

A lesson to be drawn from this story is clear enough, but it is instructive to consider how slow the Church has been to learn it:

Peter represents the Church in an official and authorized capacity. No matter how Christians variously interpret Jesus’ mandate to him—

“I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 16:19)

—they have long recognized in Peter’s ministry an “institutional” aspect. He represents the Christian body in an “official” capacity. It is Peter’s name at the top of the Church’s stationery, so to speak.

As believers are accustomed to regard the ministry of Paul as “prophetic,” and that of John as “contemplative,” so they are disposed to see in Peter a certified spokesman for the “official” Church. This is hardly surprising, since in the gospels Peter habitually functions that way.

Consequently, Peter’s assumption of the sword—just hours after his “ordination” at the Last Supper—is extremely problematic. It raises the question: Is the “official” Church no different from any other worldly institutions? Are we to expect the authorized spokesmen for the Gospel to behave like other men who wield power?

It is true that few official churchmen—Pope Julius II comes to mind—have actually taken up a literal sword to assert their place among the powerful of the earth. But it is not unknown for those who enjoying high authority in the Church to lay hold equivalent instruments.

Peter was hardly the last Church official to impose his coercive will by intimidation. When this happens, however, somebody’s ear is cut off, and the Gospel cannot be not heard.

Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon is the Archpriest of All Saints Orthodox Church in Chicago, IL.