by St. Athenagoras of Athens

A Plea For Chrisitans was written by Athenagoras (c. 176 A.D.) to the Emperors Marcus Aurelius and his son Commodus as a philosophical appeal for justice on behalf of the Christians. In this work, Athenagoras endeavors to show the emperors that the ill-treatment of the Christians is entirely unreasonable. This is the first philosophical demonstration of the unity of God in Christian literature. He also sets forth the doctrine of the Trinity.

A Plea For Chrisitans was written by Athenagoras (c. 176 A.D.) to the Emperors Marcus Aurelius and his son Commodus as a philosophical appeal for justice on behalf of the Christians. In this work, Athenagoras endeavors to show the emperors that the ill-treatment of the Christians is entirely unreasonable. This is the first philosophical demonstration of the unity of God in Christian literature. He also sets forth the doctrine of the Trinity.

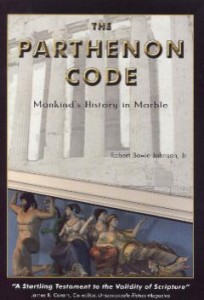

The reason for excerpting these chapters is the remarkable claim, and proofs, which are very similar to Robert Bowie Johnson’s thesis in The Parthenon Code: Mankind’s History in Marble. Johnson’s reasoning and conclusions are compelling, and I find that Athenagoras has already laid the clear groundwork for the very same idea: The pagan gods are simply the deified men and women of the past. Johnson goes further, stating that they are, in fact, the Biblical characters of Genesis, but from the point of view of those who reject God and His Laws, and would make themselves “like God.” I don’t get anything for recommending The Parthenon Code, but I do suggest you read it.

The reason for excerpting these chapters is the remarkable claim, and proofs, which are very similar to Robert Bowie Johnson’s thesis in The Parthenon Code: Mankind’s History in Marble. Johnson’s reasoning and conclusions are compelling, and I find that Athenagoras has already laid the clear groundwork for the very same idea: The pagan gods are simply the deified men and women of the past. Johnson goes further, stating that they are, in fact, the Biblical characters of Genesis, but from the point of view of those who reject God and His Laws, and would make themselves “like God.” I don’t get anything for recommending The Parthenon Code, but I do suggest you read it.

THE HEATHEN GODS WERE SIMPLY MEN

But it is perhaps necessary, in accordance with what has already been adduced, to say a little about their names. Herodotus, then, and Alexander the son of Philip, in his letter to his mother (and each of them is said to have conversed with the priests at Heliopolis, and Memphis, and Thebes), affirm that they learnt from them that the gods had been men. Herodotus speaks thus:

“Of such a nature were, they said, the beings represented by these images, they were very far indeed from being gods. However, in the times anterior to them it was otherwise; then Egypt had gods for its rulers, who dwelt upon the earth with men, one being always supreme above the rest. The last of these was Horus the son of Osiris, called by the Greeks Apollo. He deposed Typhon, and ruled over Egypt as its last god- king. Osiris is named Dionysus (Bacchus) by the Greeks.”

“Almost all the names of the gods came into Greece from Egypt.”

Apollo was the son of Dionysus and Isis, as Herodotus likewise affirms:

“According to the Egyptians, Apollo and Diana are the children of Bacchus and Isis; while Latona is their nurse and their preserver.”

These beings of heavenly origin they had for their first kings: partly from ignorance of the true worship of the Deity, partly from gratitude for their government, they esteemed them as gods together with their wives.

“The male kine, if clean, and the male calves are used for sacrifice by the Egyptians universally; but the females, they are not allowed to sacrifice, since they are sacred to Isis. The statue of this goddess has the form of a woman but with horns like a cow, resembling those of the Greek representations of Io.”

And who can be more deserving of credit in making these statements, than those who in family succession son from father, received not only the priesthood, but also the history? For it is not likely that the priests, who make if their business to commend the idols to men’s reverence, would assert falsely that they were men. If Herodotus alone had said that the Egyptians spoke in their histories of the gods as of men, when he says,

“What they told me concerning their religion it is not my intention to repeat, except only the names of their deities, things of very trifling importance,”

it would behove us not to credit even Herodotus as being a fabulist. But as Alexander and Hermes surnamed Trismegistus, who shares with them in the attribute of eternity, and innumerable others, not to name them individually,[declare the same], no room is left even for doubt that they, being kings, were esteemed gods.

it would behove us not to credit even Herodotus as being a fabulist. But as Alexander and Hermes surnamed Trismegistus, who shares with them in the attribute of eternity, and innumerable others, not to name them individually,[declare the same], no room is left even for doubt that they, being kings, were esteemed gods.

That they were men, the most learned of the Egyptians also testify, who, while saying that ether, earth, sun, moon, are gods, regard the rest as mortal men, and the temples as their sepulchres. Apollodorus, too, asserts the same thing in his treatise concerning the gods. But Herodotus calls even their sufferings mysteries.

“The ceremonies at the feast of Isis in the city of Busiris have been already spoken of. It is there that the whole multitude, both of men and women, many thousands in number, beat them selves at the close of the sacrifice in honour of a god whose name a religious scruple forbids me to mention.”

If they are gods, they are also immortal; but if people are beaten for them, and their sufferings are mysteries, they are men, as Herodotus himself says:

“Here, too, in this same precinct of Minerva at Sais, is the burial-place of one whom I think it not right to mention in such a connection. It stands behind the temple against the back wall, which it entirely covers. There are also some large stone obelisks in the enclosure, and there is a lake near them, adorned with an edging of stone. In form it is circular, and in size, as it seemed to me, about equal to the lake at Delos called the Hoop. On this lake it is that the Egyptians represent by night his sufferings whose name I refrain from mentioning, and this representation they call their mysteries.”

And not only is the sepulchre of Osiris shown, but also his embalming:

“When a body is brought to them, they show the bearer various models of corpses made in wood, and painted so as to resemble nature. The most perfect is said to be after the manner of him whom I do not think it religious to name in connection with such a matter.”