by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

During the past decade or so there has been a renewed interest in what we may call a philosophical reading of the Bible. By this I mean the reflective study of Holy Scripture, not necessarily as God’s revelatory Word, but as a philosophical resource, an ancient expression of inherited wisdom. In 2003 two distinguished scholars—both of them students of Leo Strauss—adopted this approach to Holy Scripture in two engaging but very different books: The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis, by Leon R. Kass, and Political Philosophy and the God of Abraham, by Thomas L. Pangle

During the past decade or so there has been a renewed interest in what we may call a philosophical reading of the Bible. By this I mean the reflective study of Holy Scripture, not necessarily as God’s revelatory Word, but as a philosophical resource, an ancient expression of inherited wisdom. In 2003 two distinguished scholars—both of them students of Leo Strauss—adopted this approach to Holy Scripture in two engaging but very different books: The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis, by Leon R. Kass, and Political Philosophy and the God of Abraham, by Thomas L. Pangle

Not all parts of Holy Scripture, of course, lend themselves equally to this approach. It is particularly congenial to the Wisdom Books, notably Proverbs, Job, and Qoheleth. In these books we find investigations into the pursuit of wisdom that do not (or not often) invoke the core historical themes of Holy Scripture: Redemption and Covenant. Because of their sustained appeal to general human experience, the Wisdom Books invite the reader into a broad meditative discussion of the human condition.

For example, the several characters in the Book of Job serve as the voices for specific “schools” of Philosophy. Likewise, the inner struggles of Qoheleth form a sort of dialogue about the major questions of human existence. The Wisdom Books, moreover, by entertaining divergent views on philosophical questions, encourage the reader to work through a dialectical process that respects their complexity.

In a sense, Israel’s Wisdom tradition was born of that intellectual effort. From the beginning, it had a wide, ecumenical character, open to discussion outside the community of faith. Moses, even before leading the Chosen People to the experience of Sinai,

“was learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians” (Acts 7:22). As for Solomon, “he was wiser than all men—than Ethan the Ezrahite, and Heman, and Chalcol, and Darda, the sons of Mahol” (1 Kings 4:31).

The complexity and the breadth of perspective in the Wisdom Literature are less discernible in other parts of Holy Scripture; I think particularly of the large defining narrative of God’s People. The endeavor to find general, universally available perspectives and moral paradigms in the Torah and the Former Prophets needs to be circumspect. For instance, even the “universal moral norms” of the Decalogue begin with a very specific declaration and historical claim,

“I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage” (Exodus 20:2).

If someone wants to find a broad, discursive approach to philosophical concerns, he should probably avoid Sinai, nor does he need to consult with Elijah.

Neglect of these literary differences within the biblical canon accounts for a certain unevenness within some modern works devoted to the philosophical study of Holy Scripture.

A recent example is The Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture by Yoram Harzony, which appeared earlier this year. Endeavoring to demonstrate “both that the Hebrew Bible can be fruitfully read as a work of reason, and how the Hebrew Bible can be read as a work of reason,” Harzony illustrates his thesis by examining concrete examples across the range of the Hebrew Canon.

This approach understandably works best when applied to those parts of the Scriptures that analyze psychological experience without a restrictive reference to concrete historical events. Arguably the best chapter of Harzony’s work is devoted to Jeremiah’s analysis of knowledge. He argues convincingly that the Prophet’s reflections are close to

“Plato’s conception of human beings as constantly set upon by illusions that take hold of them and set their course.”

Because Israel’s history is so unique, however, Harzony’s approach is less convincing with respect to the Torah and the Former Prophets, where he is forever looking for applicable moral lessons. In these narratives, however, the interest of the biblical author is mainly in God’s activity, not man’s. In the story of the Davidic monarchy, for example, Harzony discovers the beginnings of a “limited state,” with features similar to a constitutional monarchy. Hardly so, I think. Let him test the theory by consulting texts like Psalm 89 (Greek 88), a poem that integrates the historical Davidic covenant into the constitutive structure of the cosmos itself.

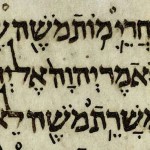

The central core of the biblical literature is inseparable from the uniqueness of Israel’s experience and the uniqueness of Israel’s God. I can agree with Harzony’s declaration that “the word of God is continuous with human reason and wisdom,” but only in the sense that the children of Israel have the same humanity as the rest of us. The Hebrew Scriptures, however, are specifically Hebrew; if God had spoke in another language, it would have been another message, because the uniqueness of Israel cannot be cut away from Israel’s Sacred Literature.

However God’s choice of Israel is to be understood, it was a choice. After the confusion of the tongues on the Plains of Shinar, the Almighty was obliged—so to speak—to pick a tongue in which to address the human race. When He chose Hebrew, He necessarily chose the people who spoke it. When He entered into their history by Redemption and Covenant, He caused His message to be written into their literature. This is why the truth conveyed in Holy Scripture is necessarily the hebraica veritas.