by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

In John’s Gospel the freedom of Jesus, with respect to his death, is truly thematic; no one has power over Jesus. We observe, for instance, John’s surprising description of his arrest, in which he appears in majesty and with full command:

“Then Judas, having received a military detachment and officers from the chief priests and Pharisees, approached with lanterns, torches, and weapons. Jesus therefore, aware of all things that would come upon him, went forward and said to them, ‘Whom are you seeking?’ They answered him, ‘Jesus of Nazareth.’ Jesus said to them, ‘I AM.’ (And Judas, who betrayed him, also stood with them.) Now when he said to them, ‘I AM,’ they drew back and fell to the ground.”

So much is Jesus “in charge” of the situation in the garden that he is obliged, as it were, to order his captors to arrest him!

“Then he asked them again, ‘Whom are you seeking?’ And they said, ‘Jesus of Nazareth.’ Jesus answered, ‘I have told you that I AM. Therefore, if you seek me, let these go their way.'”

At this point in the story John includes an ironic detail that we know from the other gospels: Peter’s impetuous action to protect the Savior:

“Simon Peter, having a sword, drew it and struck the high priest’s servant, cutting off his right ear.”

Then Jesus, in restraining his well-intentioned apostle, declares the freedom of his acquiescence to the arrest. Whereas in the other Gospels Jesus prays that he might be spared the cup of the Passion, here in John there is not the slightest hesitation in his resolve to drink it:

“Shall I not drink the cup which my Father has given Me?”

This assertion of Jesus’ power over his own life or death is consistent with his query in Matthew’s account:

“Or do you think that I cannot now pray to my Father, and He will provide me with more than twelve legions of angels?”

Jesus declares this freedom emphatically:

“For this reason my Father loves me: because I lay down my life that I may take it again. No one snatches it from me, but I lay it down of myself. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it again. This command I have received from my Father (John 10:17-18).”

Reflecting on this dominical affirmation, Christians have traditionally inferred that the humanity assumed by God’s Son was not, like ours, in bondage to death. That is to say, his humanity, hypostatically united to the divine nature, was not obliged to die; he was not subject, or subjugated, to sin and death. There was no physical necessity for him to perish; the power of death was not in him. Consequently, when Jesus laid down his life, he did so by his own consent, freely and as an act of obedience to his Father:

“This command I have received from my Father.”

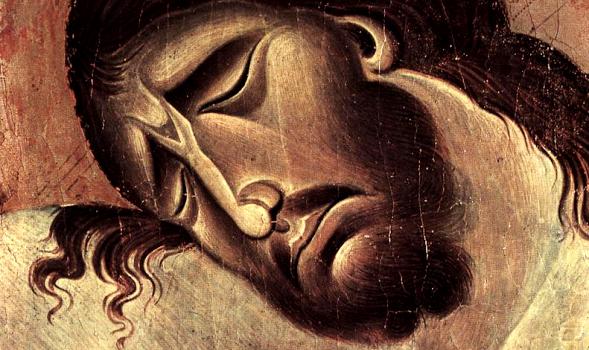

At the same time, nonetheless, orthodox Christian theology insists that Jesus was able to die; this is inferred from the fact that he consented to die. Consequently, the ancient catholic Fathers maintained, against various heretics, that his death was real, not apparent. What the eyewitnesses beheld on Calvary was a true death; the fact of it pertained to the faith once delivered to the saints:

“I delivered to you, as of primary importance, what I also received: that Christ died . . .” (1 Corinthians 15:3).

Inasmuch as he died without a physical necessity to die, Jesus’ humanity was like that of Adam before the Fall: physically able to die but not subjected to death. Indeed, the early Christians were very sensitive to certain theological parallels and contrasts between Jesus and Adam with respect to death.

If, however, there was no physical necessity for Jesus to die, how do we interpret the many biblical references to a “must”—dei—with respect to his death? This is not an easy question. If there was no physical reason for Jesus to die, how are we to understand the necessity of his death?

Was there what might be called a “metaphysical” necessity for Jesus to die? Was there some inherent postulate in rebus—for example, a compelling principle of eternal justice, a structural predicate within the created universe, or, as Saint Anselm believed, a transcendent obligation imposed by God’s offended honor—that required God’s Son to die? Put another way, did the “necessity” of Jesus’ death resemble the logical rigor requiring four to be inferred from the conjunction of two and two? Were the means of the Atonement so metaphysically determined that it could not have been accomplished in any other way?

Times out of mind I have heard Christians respond that God could have chosen any number of ways to effect the Atonement. Let me say I quake at the audacity of this suggestion. These folks have no way of knowing this to be the case. Indeed, I regard all such speculations as attempts to go around Christology; they endeavor to examine divine thought apart from the actual revelation of that thought in the Gospel.

I have no confidence in human speculations about divine thought on this or any other matter. All I know of God, I know from His Word, and I don’t see a thing in His Word that throws the faintest light on how God thinks about questions like this. I am unable to picture Him as a great cosmic wizard with a collection of possible tricks up His sleeve. For this reason, I am unable to judge the merits of any speculation about whether or not, in the eternal mind and almighty will of God, Jesus had to die by crucifixion. Respectfully, we don’t know beans about how the Atonement might otherwise have been accomplished than it was, in fact, accomplished: the Agony in the Garden, the rejection by Israel, the scourging at the pillar, the crowning with thorns, the mockery and taunts, the depths of spiritual dejection, the darkness—all of it.

I suggest that the “must” experienced by Jesus, which in no way impaired his freedom, may be best interpreted in the sense of destiny. That is to say, the “must” felt by Jesus, with respect to his vocation, had to do with his morally compelling discernment of God’s diachronic, covenantal plan as it was revealed in the concrete, particular, and defining circumstances of his place and role in the history of Israel: passus sub Pontio Pilato.

I should continue with the comment that destiny is to be distinguished from predestination. Predestination is necessarily predicated from above events; destiny is perceived within events. Whereas the concept of predestination has to do with the divine foreknowledge and prior determination, destiny is an experienced assertion recommended by concrete reality, which human beings perceive within the restricting circumstances of time and place, and according to their discernment of vocation. Predestination is invariably expressed in a thesis, whereas destiny is discerned in a morally enlightened sense, perhaps akin to prophecy.

In short, when Jesus asserted,

“This command I have from my Father,”

he was not affirming a metaphysical thesis but his reflective analysis of God’s will and intent as revealed to him within the changing and dramatic circumstances that led to the Cross. He knew what God wanted of him in the actual context of that time in Israel’s history.

His vocation was inseparable from the impending tragedy of that history; even the details of his death were determined:

“He began to teach them that the Son of Man must (dei) suffer many things, and be rejected by the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed.”

Was there some other way, in those concrete circumstances, for the Atonement to be accomplished?

No, there wasn’t. This was the hour, and he was the man.

The cup had to be drunk . . . freely.