By Jonathan Pageau

Ever wonder about the staff carried by Orthodox bishops, and why it has two serpents on it? Read and learn!

(I)t happened that I fell into a sin very dangerous to my soul. But as it was not in my habit to hide a serpent in the depths of my heart, I seized it by the tail and found it immediately to be a doctor.

St-John Climacus citing a monk. Ladder of Divine Ascent

One of the most surprising images one is faced with considering Orthodox liturgical symbolism is the bishop’s staff sporting two snakes flanking a small cross atop it. Especially in a Protestant North American context, this image seems to hark back to ancient chthonian cults, more a wizard’s magic staff than anything Christian. As I have been doing for other subjects, I would like to take a trip through iconography, through the Bible and other traditions to show how this symbol is all at once thoughtful, powerful and perfectly orthodox in the broadest sense. It also happens to fit nicely with all I have been writing for the OAJ up till now.

One of the most surprising images one is faced with considering Orthodox liturgical symbolism is the bishop’s staff sporting two snakes flanking a small cross atop it. Especially in a Protestant North American context, this image seems to hark back to ancient chthonian cults, more a wizard’s magic staff than anything Christian. As I have been doing for other subjects, I would like to take a trip through iconography, through the Bible and other traditions to show how this symbol is all at once thoughtful, powerful and perfectly orthodox in the broadest sense. It also happens to fit nicely with all I have been writing for the OAJ up till now.

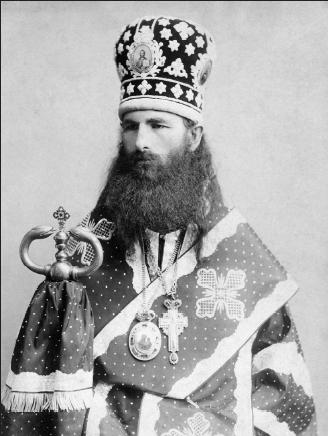

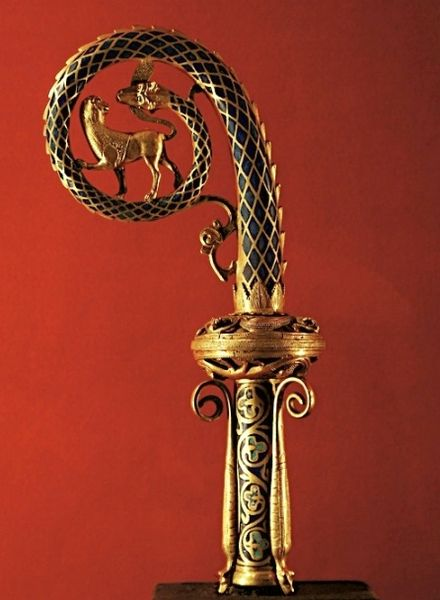

The first hurdle we must overcome is the perception that the Western bishop’s staff, the crosier, is really a shepherd’s staff, whereas the Orthodox have this strange snake bearing object. In fact, for a millennia at least, the western crosier was also identified with a serpent as medieval crosiers attest.We could say that there are two basic shapes, the crosier and the “tau” shaped staff which were present in the Church before the Schism, both of these shapes have been interpreted with serpents. The current Orthodox version of the staff with serpents(as seen above with Bishop Vladimir Sokolovsky) is a variation of these models.

Tau shaped serpent crozier from Koeln, Germany, circa 1000.

We wonder though, how can such an image of serpents, both in the East and West be appropriate for the very symbol of a Bishop’s authority? Many will point to the Biblical story of the bronze serpent, somehow prefiguring Christ, as the basis for this use of serpents on the bishop’s staff. This is a perfectly sound explanation, though it is insufficient to create a complete picture. If we are to look a Moses as the origin of this image, we should look earlier. The very first time we encounter a staff in the Bible, at least a staff that is related to divine authority, is at the burning bush. When Moses doubts the Pharaoh will listen to him, God tells him:

“What is that in your hand?” He said, “A rod.” And He said, “Cast it on the ground.” So he cast it on the ground, and it became a serpent; and Moses fled from it. Then the Lord said to Moses, “Reach out your hand and take it by the tail” (and he reached out his hand and caught it, and it became a rod in his hand), Exodus 4:1-3

The very first time we encounter a staff of divine authority, it is immediately linked to a serpent. Here we find a first example of the “shiftiness” of the snake symbol, of its dual nature. In the story of Moses and pharaoh there are two origins of the serpents. We know that Pharaoh’s magicians could produce the same miracle, and so both sides make serpents from staffs, a “good” serpent and a “bad” serpent. The good one eats the bad one.

The shiftiness, the double sided aspect of the serpent symbol appears also in the story of the bronze serpent on several levels. The Israelites had been plagued by serpents, and to save them from the poisonous bites, God told Moses to make a bronze serpent and to put it on a staff. Whoever would look to the bronze serpent would be healed, yet those refusing to do so would die of their snake bite.

In terms of duality, we can see clearly here how the serpent is both the disease and cure. Looking to the serpent that was “raised up” will cure one from those serpents that bite “down below”, just as an antidote is made from the poison or a vaccine is made from the disease. Another way to see the duality in the story is how this serpent that was raised up as a healing device, will later be “cast down” by the virtuous king Hezekiah for having become an idol (2 Kings 18:4).

With the bronze serpent we understand the serpent is not only related to a staff, but also more generally to the “vertical”, the pole, the ladder, the axis. The staff is only one facet of this vertical symbol. The first and primal version of this symbol is of course the tree. So we must reach further back than Moses in the Biblical text, looking to one of the very first mentions of a specific tree: the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil in the middle of the garden. With this tree we find the serpent, and in Christian iconography, it has been represented unanimously as coiled around the Tree of knowledge as it entices Adam and Eve to eat from its fruit.

[…]

Read the entire article on the Orthodox Arts Journal website.

Source: Orthodox Arts Journal | HT: Monomakhos