by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

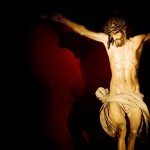

The New Testament teaches that Jesus gave up his life and handed himself over to unspeakable suffering for the sake of those he loved. Thus, in the Last Supper discourse he declared:

The New Testament teaches that Jesus gave up his life and handed himself over to unspeakable suffering for the sake of those he loved. Thus, in the Last Supper discourse he declared:

“This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you. No one has greater love than to lay down (thei) his life on behalf of (hyper) his friends. . . No longer do I call you servants . . . but I have called you friends.”

Here Jesus takes up the affirmation contained in his Good Shepherd parable:

“I am the Good Shepherd. The Good Shepherd lays down (tithesin) his life for (hyper) the sheep. . . . As the Father knows me, even so I know the Father, and I lay down (tithemi) my life for (hyper) the sheep.”

In these Johannine texts two points of vocabulary are particularly to be noted:

First, in respect to the verb, which I have translated as, “lay down,” it is a form of the Greek root the-, which normally means, “to place,” or “to set.” In this idiomatic context, however, the verb is better translated as “to give” or “to lay down.” Although either translation is accurate enough, I have chosen “lay down” because Christian piety, as far as I can tell, has traditionally tended to favor it.

Second, in respect to the preposition, (hyper) which I have translated as “for,” it has the sense of “for the sake of,” or “on behalf of,” or “unto the benefit of.” The Apostle John has this affirmation in mind when he writes of Jesus,

“By this we know love, because he laid down his life for our sake (hyper hemon)” (1 John 3:16).

In respect to Jesus laying down his life, John narrates the ironic “prophecy” uttered by Caiaphas the high priest. After the raising of Lazarus, we recall, the Sanhedrin expressed concern that

“everyone will believe in him, and the Romans will come and will abolish both our place and nation.”

In response to this concern Caiaphas declared:

“You know nothing whatever, nor do you consider that it is expedient for us that one man should die for (hyper) the people, and not that the whole nation should perish.”

Whereas Caiaphas recommended the murder of Jesus as a political expedient, the Evangelist perceived a deeper and more significant meaning to his words. He realized that the cynical declaration of Caiaphas was, in fact, freighted with the drama of prophecy:

“Now he did not say this on his own, but, being high priest that year, he prophesied that Jesus would die for the sake of (hyper) the nation, and not for the sake of (hyper) that nation only, but also that he would gather together into one the scattered children of God.”

In these affirmations about Jesus’ death we recognize the root of the early Christian conviction that Christ died for us, on our behalf, for our sake, unto our benefit—hyper hemon. Thus, the Apostle Paul summed up the redemptive work of grace:

“While we were yet powerless, Christ died, at the chosen time, for the sake of (hyper) the ungodly. Indeed, scarcely for (hyper) a righteous man will someone die, though on behalf of (hyper) a good man someone might even dare to die. But God demonstrates His love in our regard, in that while we were yet sinners, Christ died for our sake (hyper hemon).”

Although classical literature often speaks of someone’s dying for—or risking one’s life for—the sake of someone else, in the Old Testament the idea does not appear often enough to be called a theme.

A notable instance, however, is found in 2 Samuel 23; it is a story of three warriors who put their lives in danger by raiding a Philistine camp at Bethlehem in order to obtain water for David to drink. David, deeply touched by the feat, pours out the water as a libation to the Lord, since it was obtained at the risk of men’s lives. In David’s eyes this water represented their life’s blood:

“And he said, ‘Far be it from me, O Lord, that I should do this! Isn’t this the blood of the men who went with their lives’ [hadam ha’anashim haholakim benaphshotam]. Therefore he would not drink it” (23:17).

It is important to observe that this is the language of sacrifice—in the strict sense of a ritual offering: The water is poured out in libation as a poetic symbol of blood. Inasmuch as these men placed their lives in jeopardy to obtain the water, the latter represented their life’s blood. Consequently, it fell under the Law’s ban against the drinking of blood (cf. Leviticus 17:10).