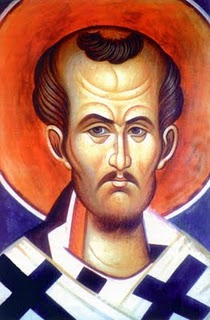

By John Sanidopoulos

St. John Chrysostom probably more than any other Father of the Church speaks about the “wrath of God” and “divine punishment”. Most who read these passages often do so through the lenses of western medieval or reformation theology, even many Orthodox Christians, who are unable to read the depths of the spirit behind the letter. The reason for this is because, as St. Symeon the New Theologian explains, when speaking about matters of divine judgement,

“the interpretation is difficult because it is not about things which are present and visible, but about future and invisible matters. There is therefore great need of prayer, of much ascetic effort, of much purity of the nous, both in us who speak and in those who listen, in order for the first to be able to know and speak well and for the others to listen with understanding to what is said.”

Therefore, those of a carnal, simplistic and overly literal understanding of these passages fail to understand the depth of divine judgement, inflicting upon the nature of God human-like passions, which is exactly what the ancient pagans did with their gods in order to make the impassioned state not only a natural state, but to deify it as well.

Fortunate for us, outside of the fiery sermons and exegetical works of the divine Chrysostom, we also have pastoral moments in which he personally guides his spiritual children and friends to the deeper understanding of spiritual matters. One such case is in his First Exhortation to Theodore After His Fall. This is a beautiful letter by Chrysostom to Theodore of Mopsuestia, who was fascinated by a woman and sought marriage despite his monastic vow of celibacy, and with Chrysostom’s help overcame the despair of such a conflict. In order to lead Theodore out of despair, he explains that there is no sin greater than despair, yet if it were true that God in His nature were wrathful and punishing, then despair should naturally overtake us. Yet this is not the case, as he explains:

“For if the wrath of God were a passion, one might well despair as being unable to quench the flame which he [a wicked man] had kindled by so many evil doings; but since the Divine nature is passionless, even if He punishes, even if He takes vengeance, He does this not with wrath, but with tender care, and much loving-kindness; wherefore it behooves us to be of much good courage, and to trust in the power of repentance.

For even those who have sinned against Him He is not wont to visit with punishment for His own sake; for no harm can traverse that Divine nature; but He acts with a view to our advantage, and to prevent our perverseness becoming worse by our making a practice of despising and neglecting Him. For even as one who places himself outside the light inflicts no loss on the light, but the greatest upon himself being shut up in darkness; even so he who has become accustomed to despise that almighty power, does no injury to the power, but inflicts the greatest possible injury upon himself.

And for this reason God threatens us with punishments, and often inflicts them, not as avenging Himself, but by way of attracting us to Himself. For a physician also is not distressed or vexed at the insults of those who are out of their minds, but yet does and contrives everything for the purpose of stopping those who do such unseemly acts, not looking to his own interests but to their profit; and if they manifest some small degree of self-control and sobriety he rejoices and is glad, and applies his remedies much more earnestly, not as revenging himself upon them for their former conduct, but as wishing to increase their advantage, and to bring them back to a purely sound state of health.

Even so God when we fall into the very extremity of madness, says and does everything, not by way of avenging Himself on account of our former deeds; but because He wishes to release us from our disorder; and by means of right reason it is quite possible to be convinced of this.”

So when Holy Scripture speaks of divine wrath, punishment and vengeance, this is language that does not necessarily describe the unknowable, incomprehensible and unspeakable nature of God, but rather its aim is to prevent man from remaining in his wickedness and to repent. The wrath of God is described by Chrysostom as the loving-kindness of God towards man, yet the wicked experience this love unto salvation as wrath and punishment. He uses the analogy of a physician, and how the treatment of a certain illness by a physician is not done to punish the one who causes the illness or even suffers from it, but by any means necessary to bring health and well-being to the one in need of treatment no matter how much pain it may inflict. Thus, through the use of these “riddles” God uses language like this in Scripture for us to comprehend how serious it is to repent now, since, according to the Holy Fathers, after death there is no repentance.

“For consider I pray the condition of the other life, so far as it is possible to consider it; for no words will suffice for an adequate description: but from the things which are told us, as if by means of certain riddles, let us try and get some indistinct vision of it.”

Having said these things, Chrysostom goes on to describe the future judgment for Theodore to truly visualize it, even though the language used is a “riddle”,

“for no words will suffice for an adequate description”.