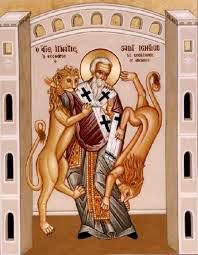

It’s a bit anachronistic to speak of St. Ignatius of Antioch (died about 117 A.D.) and Trinitarian theology as the doctrine of the Trinity developed in the first centuries of Christianity and its associated terminology was finalized in the third and fourth centuries as a reflection of the realities it had experienced. J.N.D. Kelly explains that the monotheistic faith Christianity had inherited from Judaism had to be integrated with “the fresh data of the specifically Christian revelation. Reduced to their simplest, these were the convictions that God had made Himself known in the Person of Jesus, the Messiah, raising Him from the dead and offering salvation to men through Him, and that He had poured out His Holy Spirit on the Church” (Early Christian Doctrines, pp. 87-88). Kelly’s book is an excellent resource to see how the Church’s understanding of the relationship between Father, Son, and Holy Spirit developed in the early Church.

It’s a bit anachronistic to speak of St. Ignatius of Antioch (died about 117 A.D.) and Trinitarian theology as the doctrine of the Trinity developed in the first centuries of Christianity and its associated terminology was finalized in the third and fourth centuries as a reflection of the realities it had experienced. J.N.D. Kelly explains that the monotheistic faith Christianity had inherited from Judaism had to be integrated with “the fresh data of the specifically Christian revelation. Reduced to their simplest, these were the convictions that God had made Himself known in the Person of Jesus, the Messiah, raising Him from the dead and offering salvation to men through Him, and that He had poured out His Holy Spirit on the Church” (Early Christian Doctrines, pp. 87-88). Kelly’s book is an excellent resource to see how the Church’s understanding of the relationship between Father, Son, and Holy Spirit developed in the early Church.

Fr. Edmund Fortman gives this analysis which shows the high view St. Ignatius had of the Son and Holy Spirit:

Ignatius delves more deeply into some matters than do the other Apostolic Fathers and adds his personal reflections but without developing any systematic theology.1

The core of his thought is the divine ‘economy’ in the universe. God wished to save the world and humanity from the despotism of the prince of this world. And so He ‘manifested Himself in Jesus Christ His Son, who is His Word proceeding from silence, and who in all things was pleasing to Him who sent Him’ (Magn. 8.2). ‘Our God, Jesus the Christ, was born of Mary . . . of the seed of David and of the Holy Spirit’ (Eph. 18.2). He ‘was truly crucified and died. . . and was truly raised from the dead when His Father raised Him’ (Trall. 9).

For Ignatius God is Father, and by ‘Father’ he means primarily ‘Father of Jesus Christ’ : ‘There is one God, who has manifested Himself by Jesus Christ His Son’ (Magn. 8.2). Jesus is called ‘God’ 14 times (Eph. inscr. 1.1, 7.2, 15.3, 17.2, 18.2, 19.3; Trall. 7.1; Rom. inscr. 3.3, 6.3; Smyrn. 1.1; Pdyc. 8.3). He is the Father’s Word (Magn. 8.2), ‘the mind of the Father’ (Eph. 3.3), and ‘the mouth through which the Father truly spoke’ (Rom. 8.2). He is ‘His only Son’ (Rom. inscr.), ‘generate and ingenerate, God in man . . . son of Mary and Son of God . . . Jesus Christ our Lord’ (Eph. 7.2). He is the one ‘who is beyond time the Eternal the Invisible who became visible for our sake, the Impalpable, the Impassible who suffered for our sake’ (Polyc. 3.2).

It has been said that for Ignatius Jesus’ ‘divine Sonship dates from the incarnation,’ 2 and that he ‘seems rather to ascribe the divine sonship of Jesus to the fact that Mary conceived by the operation of the Holy Spirit.’ 3 If he did date Jesus’ sonship from the incarnation he did not thereby deny His pre-existence. For he declared very definitely that Jesus Christ ‘from eternity was with the Father and at last appeared to us’ (Magn. 6.1) and that He ‘came forth from one Father in whom He is and to whom He has returned’ (Magn. 7.2). But just how He was distinct from the Father, since both are God, Ignatius does not say. Perhaps he hints at an answer when he says that Christ is the Father’s ‘thought’ (Eph. 3.2).

While Ignatius concentrated most of his thought on Christ, he did not ignore the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit was the principle of the Lord’s virginal conception (Eph. 18.2). Through the Holy Spirit Christ ‘confirmed . . . in stability the officers of the Church’ (Phil. inscr.). This Spirit spoke through Ignatius himself (Phil. 7.1). Ignatius does not cite the Matthean baptismal formula, but he does sometimes mention Father. Son, and Holy Spirit together. He urges the Magnesians to ‘be eager . . . to be confirmed in the commandments of our Lord and His apostles, so that “whatever you do may prosper” . . . in the Son and Father and Spirit’ (Magn. 13.2). And in one of his most famous passages he declares: ‘Like the stones of a temple, cut for a building of God the Father, you have been lifted up to the top by the crane of Jesus Christ, which is the Cross, and the rope of the Holy Spirit’ (Eph. 9.1). Thus although there is nothing remotely resembling a doctrine of the Trinity in Ignatius, the triadic pattern of thought is there, and two of its members, the Father and Jesus Christ, are clearly and often designated as God.

It has been urged 4 that for Ignatius there is no Trinity before the birth of Jesus, but that before the birth there was only God and a pre-existent Christ, who is called either Logos or Holy Spirit. There is, however, no solid evidence that Ignatius either in intention or in words made any such identification either in his letter to the Smyrnaeans (inscr.) or in that to the Magnesians (13.1,2). On the contrary. when Ignatius writes that ‘our God, Jesus Christ, was born of Mary . . . and of the Holy Spirit’ (Eph. 18.2), he seems to indicate that before this birth both ‘our God Jesus Christ’ and the Holy Spirit pre-existed distinctly and that thus there was a Trinity before His birth.

Notes:

1. Quasten, Patrology, 1 : 63-76; Lawson, A Theological and Historical Introduction to the Apostolic Fathers, pp. 101-152.

2. J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines (New York and London. 1965), p. 92.

3. J. Tixeront, History of Dogmas (3 vols. St. Louis, 1910) 1 : 123.

4. Wolfson, The Philosophy of the Church Fathers, pp. 184, 191.

Taken from The Triune God: A Historical Doctrine of the Doctrine of the Trinity by Edmund J. Fortman, pp. 38-40.

HT: Orthocath