by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon is pastor of All Saints Antiochian Orthodox Church in Chicago, Illinois, and a Senior Editor of Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity.

Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon is pastor of All Saints Antiochian Orthodox Church in Chicago, Illinois, and a Senior Editor of Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity.

Psalm 91 (Greek and Latin 90) has always ranked among the more favorite and popular psalms of the Christian people, a fact that surely has something to do, in the East, with its being the opening psalm of the funeral service in the Orthodox Church.

It is also one of the very few psalms about which everyone in antiquity agreed that it should be prayed each day of the week. For all that, Christians have shown themselves less sure about exactly when, during the course of the day, this psalm should best be prayed.

Two specific periods during the day — the night and the noontide — are indicated in the psalm itself:

“You shall fear no terror of the night, nor the arrow that flies by day; neither the thing that prowls in the darkness, nor the attack of the noonday devil.”

Christians in the East, observing the references to daylight and high noon, picked this psalm to be prayed daily at the sixth hour, a custom that prevails to the present time. According to Saint John Cassian in the early fifth century, some of the monastic elders of the East understood the “noonday devil” of this psalm to be a special temptation to spiritual weariness and dejection, that mysterious despondency and distress of heart known in ascetical literature as akedia (The Institutes 10.1).

Christians in the West, on the other hand, more impressed by the references to darkness and the night, chose Psalm 91 to be prayed each evening at the canonical hour of Compline, or bedtime. For example, one finds this usage in the sixth-century monastic Rule of St. Benedict and in the traditional Roman breviary.

These two traditions, however, are not really so disparate as they seem. After all, Holy Scripture associates the noon hour — the sixth hour — not only with light, but also with darkness:

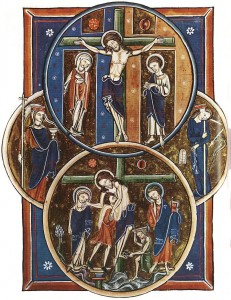

“Now when the sixth hour had come, there was darkness over the whole land until the ninth hour” (Mark 15:33).

When Christians pray each day at noon, they observe that hour in recollection of the darkness that fell as the Savior hung on the Cross.

An early witness to this custom is Hippolytus, a priest of Rome, writing about the year 210. In a work entitled The Apostolic Tradition, Hippolytus wrote:

“Pray also at the sixth hour, because when Christ was attached to the wood of the cross, the daylight ceased and became darkness. Thus you should pray a powerful prayer at this hour, imitating the cry of him who prayed and all creation was made dark for the unbelieving Jews.”

The Christian custom of praying Psalm 91 at noon, therefore, is tied to a specific moment in the Christ-event-namely, the time when Jesus, hanging on the Cross for our salvation, listened to the taunts of those who crucified Him:

“He saved others; Himself He cannot save. Let the Christ, the King of Israel, descend now from the cross, that we may see and believe” (Mark 15:31-32).

This Christological reference, based the actual narrative of the Gospels, provides an important element in the interpretation of this psalm. The enemies envisioned in this prayer are the very demons who waged incessant war against Jesus and, ultimately, saw to His execution; these are “the noonday devil,” the “thing” that prowls in the darkness, the “evil,” the “scourge,” “the asp and the adder,” “the lion and the dragon.” These are the demons defeated on the Cross.

Such is the noon hour, as Jesus faced it. The three hours of darkness just before His death on the Cross evoke the three days that immediately preceded the death of the First Born:

“So Moses stretched out his hand toward heaven, and there was thick darkness in all the land of Egypt three days” (Exodus 10:22).

Each day, as the Christian prays with Jesus at noon, he encounters once again the dark mystery of the ninth plague, the satanic shadow that rises to defy God’s first recorded words,

“Let there be light” (Genesis 1:3).

Here we touch the deeper meaning of the noonday prayer — our salvation through the defeat of the demons on Calvary. John Cassian spoke of noon as that hour when

“the spotless victim, our Lord and Savior, was offered to the Father, and mounting the Cross for the salvation of the whole world He destroyed the sins of the human race.” (The Institutes 3.3.)