by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

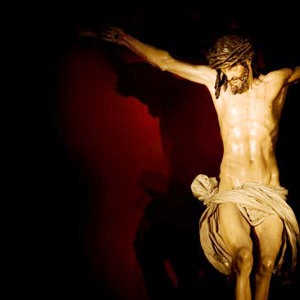

The Evangelist Mark traces to the lips of Jesus the first Christian reference to a particular and foundational theme, drawn from the Book of Isaiah: the Suffering Servant. When Jesus declared,

The Evangelist Mark traces to the lips of Jesus the first Christian reference to a particular and foundational theme, drawn from the Book of Isaiah: the Suffering Servant. When Jesus declared,

“the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many,”

this referential context was unmistakable. Here we touch on the very heart of the Atonement.

Essential to our understanding of this subject is the meaning of the noun “ransom.” In its literal and original sense this noun, lytron (along with its variant, antilytron), referred to the redemption of property, whether real estate or a slave.

This usage spawned various metaphorical references, including the “price” of a human life. Understood either literally or by way of metaphor, the earliest biblical meanings of this noun suggest a “payment” of some sort. The same is true of the cognate verbal form, lytroun, meaning to buy back, to purchase, to redeem.

Is this what Jesus meant when he spoke of giving his life as a “ransom”? Did Jesus “redeem” by paying the “price” of his life? If so—if these expressions do refer to some sort of transaction—to whom did Jesus pay this price? Since these are mercantile terms, we should probably not wonder that some readers of Holy Scripture have been disposed to think of salvation as though it were some sort of business arrangement, as though Jesus on the Cross handed over a price to a creditor in order to free us from sin and death. Various theories of redemption have been elaborated on such a model, according to which Jesus effected a transaction, paying a price—whether to the Devil or to God or to eternal justice or whatever—for man’s salvation.

I believe all these theories are misguided. They fail, in my opinion, because they by-pass the more extensive metaphorical value with which these terms are freighted in biblical language.

Let us take the nouns “redemption” or “ransom” (lyutron) and the corresponding verbs (lytroun) “redeem” in the case of the manumission of a slave. As these terms applied to the freedom of a slave, they very early came to mean any kind of liberation of a slave, whether or not an actual price was paid. That is to say, these words came to signify liberation from bondage, with no necessary suggestion of a transaction between partners.

Moreover, there was more than one kind of slavery. The Israelites, for instance, were slaves in Egypt. When the Lord “ransomed” them—when He “redeemed” them—He did not pay Pharaoh some designated sum of money. There was no commercial transaction at all. God simply raided Egypt and liberated the Israelites. In this case, ransom simply meant liberation from bondage.

Indeed, this became the normal meaning of “redeem” and “ransom” in the Bible when it is used in a religious sense, particularly when God is the subject of the verb. This is the meaning the Apostles understood when Jesus said that the Son of Man came

“to give his life a ransom for many.”

Similar comments are appropriate when Holy Scripture speaks of the blood of Jesus as the “price” for our sins. The term is a metaphor with not the slightest commercial connotation. Certainly the shedding of Jesus’ blood was the price for our sins, but it is quite inappropriate to inquire to whom the price was paid.

When used as a metaphor, especially a spiritual metaphor, the word “price” carries no mercantile reference. When a soldier dies defending his country, his death is the “price” of his country’s victory. When an athlete disciplines himself for coming competition, that exercise is the “price” he pays. We all recognize that the word “price” is used in such cases in a figurative way that does (not) indicate a commercial transaction. The price is simply paid; we would not think to ask, “to whom was the price paid?”

The blood of Jesus is the greatest price ever paid, but there is no correct answer to the question,“to whom was that price paid?”

There is no correct answer, for the simple reason that this is not a correct question. The question ignores the metaphorical and spiritual sense of the term. This is the reason that such a question is neither posed nor addressed in Holy Scripture.

For more on the Orthodox teachings on Atonement, CLICK HERE.