by Fr. Peter John Cameron, O.P.

This comes to us from John Anderson’s blog – Orthodox Ruminations. Enjoy!

This comes to us from John Anderson’s blog – Orthodox Ruminations. Enjoy!

I stumbled across this amazing little article written by a Dominican monk in the Catholic Church who is also a part of their Order of Preachers. He speaks a little about the Roman Catholic Church, but then gets into how the Church Fathers and homiletics go hand-in-hand and how we as preachers need to be informed and trained in Patristic exegesis and to live grounded in strong faith. I believe there is much to glean from this wonderful little article for anyone who is a preacher! Enjoy Fr. Peter John Cameron’s article!

In The Art of Oratorical Composition, Fr. Charles Coppens, S.J. Asserts:

Divine Providence has bestowed upon the Church, from the earliest ages of its existence, a number of men remarkable alike for their learning and for their saintly lives, who in copious writings, especially in commentaries on the Holy Scriptures, have explained the faith for all succeeding ages….Quotations from such authorities are certainly most suitable to impress upon the faithful the truth and the importance of the doctrines explained in a discourse. But, unfortunately, in these days of secular knowledge many Christians are too ignorant of Church history to appreciate such matters as they ought. (pp. 282-283)”

Of course, some may playfully contest that the impartiality of Coppens’ book is impaired by its practically patristic publication date (1885). Which is why the recent counsel of the Catechism of the Catholic Church speaks with particular cogency:

The Church, a communion living in the faith of the apostles which she transmits, is the place where we know the Holy Spirit…in the Tradition, to which the Church Fathers are always timely witnesses. (688)”

For faith is not self-generating:

You have not given yourself faith as you have not given yourself life….I cannot believe without being carried by the faith of others, and by my faith I help support others in the faith. (CCC 166)”

To this end, the Directory on the Ministry and Life of Priests insists that the priest must feel personally bound to cultivate, in a particular way, a knowledge of Holy Scripture with a sound exegesis, principally patristic, and meditated on according to the various methods supported by the spiritual tradition of the Church, in order to obtain a living understanding of love. (46)

Robert Louis Wilken, the William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of the History of Christianity at the University of Virginia, eloquently attests to the timeliness of the Fathers’ witness when he writes:

In recent years homilists, preachers, teachers and readers of the Bible have become dissatisfied with the results of historical-critical biblical scholarship. It is not that critical biblical scholarship is without value, but that a strictly historical understanding of the biblical text independent of theological or spiritual concerns has limited usefulness for the Church’s preaching and teaching and for the individual’s growth in faith….One way to rediscover the tradition of spiritual and theological interpretation of the Bible is to return to the classical sources, the commentaries and homilies that were written during the early years of the Church’s history. (“The Church’s Bible,” Crisis, Vol. 13, Num. 9, Oct. 1995, pp. 14-16)”

The Pertinence of the Fathers of the Church for Preaching

Metropolitan Emilianos Timiadis’ insightful short book, aptly entitled The Relevance of the Fathers (Brookline: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1994) provides an appropriate guide for analyzing the instrumental role of the Church Fathers in forming contemporary preaching intellectually, spiritually, pastorally, and humanly. In Timiadis’ view, contemporary people of faith need to rely on the writings of the Fathers of the Church to discover “how to interpret their thought to current new situations.” (p.81)

To preach with a reliance on the Fathers means to start from a stance of intellectual humility. Timiadis notes that the writings of the Fathers “prefer a holistic, inclusive approach. By this, they invite us to be more humble, honest and not to think we are the first to deal with this or that doctrine.” (p. 58)

The Fathers possess an exclusive authority and trustworthiness when it comes to the matter of the faith.

The Fathers are the privileged witnesses of the spirit, of the conscience and of the heart of the Church….They are the first who labored on the architectural designs of the building from the gathered material; they formulated the doctrine against ambiguous circulating versions. They are the nearest to the purity of the origins of our faith….In taking this precious material, they were able not only to preserve it unbroken and intact from any falsification and deviation, but even to develop and enlarge it, preserving the core and nucleus. (p. 67)”

The theological integrity of the Fathers appears most poignantly in their approach to Sacred Scripture. Timiadis observes that “patristics offers not only reason but also an inner intuition as the means of understanding the Bible” (p. 5). Timiadis also bemoans constrictive hermeneutical methods when he writes:

The Fathers help us tremendously in finding the counterweight to the emptiness and spiritual poverty found in many modern commentaries which under the pretext of appearing scientific, strictly critical and historical pass over the fundamental dimension of our salvation in Scripture….The patristic exegesis brings forth an indispensable corrective. (p. 56)”

From a spiritual perspective, the Fathers of the Church demonstrate the transforming force of the theological virtues. They bolster faith by manifesting the permanent relevance of Christian values.

Being guardians of the past, they at the same time live their values in order to show their everlasting significance, their relevance for every time and every place. They incarnate this past as “priests of commemoration,” filling the gap produced by the loss of authority and of stable reference in a given society….The Fathers while reminding us of the past, were revealing the renewing power of the Holy Spirit to a total new vision. They know how to communicate the old as new, as current for today, actualizing in the present the plan of God. (p. 25)”

The Fathers enhance hope by cultivating a holy mindfulness of the centrality of Christ in Liturgy and life.

Knowing that the world around them was desperately seeking a better life, by indicating the uniqueness of the Gospel, they spoke about the uniqueness of Christ, as Savior and Redeemer. To transfuse hope, a theological hope, they described the liturgical feasts as realizations of God’s promises….The Fathers, with boldness, declare that a society with its members is submerged, inundated by an ocean of sins, the gravest of which is a contempt for and the forgetting of our Creator, our God….Patristics reminds us that the time of trial and testing may also become a time of ascension and perfection. (pp. 19, 38)”

And patristics enkindles authentic charity since “for the Fathers the task of theology is spiritual edification, warming the suffering heart.” (p. 59)

The Fathers’ mode of transmittal was principally pastoral. They endeavored to present an integrated, comprehensive plan of the theological life that drew people into a deeper relationship with God – a plan that current programs of priestly formation, like Pope John Paul II’s Pastores Dabo Vobis, seek to recover. As Timiadis points out:

The great doctors of the Church had not yet distinguished between dogma, Eucharistic liturgy, worship, morals, asceticism, or mysticism. They were treating the Christian religion as a whole, as indeed it is, one and simple….The Fathers teach us wholeness, integrity, inner harmony and unity. (p. 11, 17)”

This insight applied in a particular way to the patristic conception of morality as it is ordered to happiness:

The Church Fathers understand Christian ethics as a unique aid to help in finding a meaning to life, an orientation, and a way. (p. 21)”

At the same time, the Fathers recognize their responsibility to challenge the People of God. In this respect, they come across as genuinely “liberal:”

The Fathers were encouraging Christians to live with questions for awhile without fearing that everything would fall apart….The Church Fathers inhabit a household built to endure stress…..They reconcile new ideas and confirm old views. (p. 15)”

But most of all, the Fathers cherish their God-given paternal role:

The Fathers are invested by the Holy Spirit with all that is constructive to replenish the missing elements within the members of the ecclesiastical body. They are not merely consultants, or advisers, but guides and spiritual fathers in the true sense. They know that this flock needs continuous nurture, guidance for growth, and a more accurate understanding of the Holy Scriptures, in order to solve the delicate and complicated issues which emerge in the healing of committed sins. (p. 49)”

Finally, the Church Fathers show forth their perduring relevance as astute students of human nature. In this regard, they imitate Jesus himself who “needed no one to give him testimony about human nature. He was well aware of what was in man’s heart.” (Jn 2:25) As Timiadis remarks:

The Church Fathers deeply appreciated constructive elements and teachings of the non-Christian ancient world….The Church Fathers knew human nature quite well. And they never ceased to repeat that true man is the person who overcomes fallen man in his weakness….The Fathers use a variety of language and arguments….They see with penetrating eyes an earthly existence full of contradictions….The Fathers are aware of human decline and ugliness but instead of turning their eyes away in disgust, they exalt God’s philanthropy. (pp. 33, 18)”

At the same time, the Fathers profoundly grasp the fundamental truth that only God himself satisfies the deepest longings in the human person. As the Catechism expresses it, “the desire for God is written in the human heart, because man is created by God and for God….Only in God will he find the truth and happiness he never stops searching for” (27).

Timiadis summarizes his book by saying:

The Fathers tried to permeate the inner depth of man’s world and to show the terrible vacuum and desert without any reference to God….The Fathers point at the desperate need of God, not only for the sake of the belief in his existence, but for solving all proceeding problems during our existence on earth….It is indeed astonishing how these Fathers made such a deep diagnosis with almost transhistoric eyes, seizing the roots of evils and proposing appropriate remedies….Their penetrating ability and admonitions on how to get out of impasses and complicated dilemmas is extraordinary. They have thus become our contemporaries. (pp. 92, 93)”

The integrity of both the Fathers’ writings and their lives effects a holy realism for the Church.

The Fathers transmit the conscience of the Church from one generation to the other….They show us the interaction between dogma and life, that every article of our faith is closely related to human reality. (p. 6)”

In this they realize a central insight of the Catechism:

There is an organic connection between our spiritual life and the dogmas. Dogmas are lights along the path of faith; they illuminate it and make it secure. (89)”

Moreover, the humanizing dimension of the Fathers’ influence insures that we do all things in memory of Christ:

The Fathers…[become] ‘reminders,’ directing and healing our memory….The Fathers also refer to the past but in quite different terms, and for them the past fortifies us in our fight against forgetfulness, against collective amnesia, characteristic of frequently manipulated public opinion. (p. 24)”

The Patristic Theology of Preaching

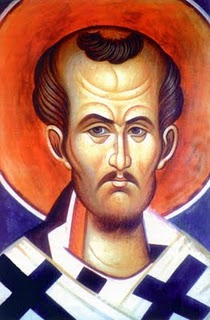

In addition to their theological message, the Fathers’ theory and theology of preaching help to overcome common obstacles in contemporary preaching so as to engender excellence. St. John Chrysostom understands preaching as a means of the priest’s sanctification:

Preaching improves me. When I begin to speak, weariness disappears; when I begin to teach, fatigue too disappears. Thus neither sickness itself nor indeed any other obstacle is able to separate me from your love….For just as you are hungry to listen to me, so too I am hungry to preach to you. My congregation is my only glory, and every one of you means more to me than anyone of the city outside….Oftentimes in my dreams I see myself in the pulpit speaking to you.”

The Fathers are unanimous in voicing the preacher’s need to be steeped in the Word of God and the teachings of the Church. Chrysostom exhorts us: “We must take great care that the Word of Christ may dwell in us richly….Let a man’s diction be beggarly and his verbal composition simple and artless, but do not let him be inexpert in the knowledge and careful statement of doctrine.” St. Augustine expresses it this way: “Know your subject matter and the words will follow.”

However, doctrinal preaching is not to be doctrinaire. Rather, effective preaching should provide practical, pastoral applications, as suggested by St. Leo the Great’s instruction on social justice:

It is not only spiritual wealth and heavenly graces that are received from God’s hands. Earthly and material riches also flow from his bounty. Therefore, it is with justice that he will demand an account of them. He has not so much given them to be possessed as put them in trust to be administered.”

The Gospel authenticity of preaching proceeds from the authenticity of the preacher’s own life of faith. St. Leo underscores how much Gospel preaching relies on fervently lived faith, and not on fancy rhetoric:

When Christ was about to summon all nations to the illumination of the faith, he chose those who were to devote themselves to the preaching of the Gospel not from among philosophers or orators, but took humble fishermen as the instruments by which he would reveal himself, lest the heavenly teaching, which was of itself full of mighty power, should seem to need the aid of words….For rhetorical arguments and clever debates of man’s device make their chief boast in this, that in doubtful matters which are obscured by the variety of opinions they can induce their hearers to accept that view which each has chosen for his own genius and eloquence to bring forward; and thus it happens that what is maintained with the greatest eloquence is reckoned the truest. But Christ’s Gospel needs not this art; for in it the true teaching stands revealed by its own light.”

As St. Augustine makes clear, the preacher who fails to manifest passion for the faith becomes a bore even to himself:

You have had to acknowledge and complain that often, because you talked too long and with too little enthusiasm, it has befallen you to become commonplace and wearisome even to yourself, not to mention him whom you were trying to instruct by your discourse, and the others who were present as listeners.”

At the same time, a pastorally sensitive preacher recognizes that there is a certain theatricality essential to preaching. St. Augustine observes:

You must not believe, brothers and sisters, that the Lord intended us to be entirely without theatrical spectacles of some kind. If there were none here, would you have come together in this place?”

Accordingly, as St. John Chrysostom explains, preaching calls for a certain creativity and ingenuity that counters the craftiness of the Evil One:

Unless the man who means to win understands every aspect of the art, the devil knows how to introduce his agents at a single neglected spot and so to plunder the flock.”

Finally, the Fathers were especially mindful and responsive to the receptivity of their congregations. St. Augustine warns against “the torpor induced by surfeit” – a problem arising from the failure to possess “due regard for the capacity and powers of our hearer and the time at our disposal.” Augustine, therefore, provides practical directives for remedying restlessness in the congregation:

It often happens that one who at first was listening gladly becomes exhausted…and now opens his mouth no longer to give assent but to yawn, and even involuntarily gives signs that he wants to depart….When we notice our hearer becoming weary, we should…say something to refresh him, and to banish uneasiness from his mind, should any breaking in upon him have begun to distract him….For faith consists not in a body bending but in a mind believing.”

In order to cultivate this process of believing, St. Gregory the Great instructs preachers to steer clear of what the congregation cannot understand:

The preacher should be sensitive to the mind of his hearer and never overtax it, for the string of the soul when stretched more than it can bear can very easily snap…For all deep things should be covered up before a multitude of hearers, and scarcely opened to a few….Every preacher should give forth a sound more by his deeds than by his words; by good living he should imprint footsteps for men to follow rather than by speaking show them the path of truth.”

In fact, the personal faith-witness of the preacher carries greater weight than we might expect. St. John Chrysostom goes so far as to say that the congregation does not sit in judgment on the sermon as muc as on the reputation of the preacher….Unless his sermons always match the great expectations formed of him, he will leave the pulpit the victim of countless jeers and complaints. No one ever takes it into consideration that a fit of depression, pain, anxiety, or in many cases anger, may cloud the clarity of his mind and prevent his productions from coming forth unalloyed; and that in short, being a man, he cannot invariably reach the same standard or always be successful, but will naturally make many mistakes and obviously fall below the standard of the real ability.

With this sobering admonition, the preacher does well to make his own the homiletic objective of St. Gregory Nazianzen:

The scope of our art is to provide the soul with wings, to rescue it from the world and give it to God, and to watch over that which is in his image—if it abides, to take it by the hand; if it is danger, to restore it; it is ruined, to make Christ dwell in the heart by the Spirit; and in a word, to deify and bestow heavenly bliss upon one who belongs to the heavenly host.”

Toward Patristically-Informed Preaching: A Sample Homily Outline

How does the preacher implement the theological message and the homiletic method of the Fathers of the Church? Here follows one example of a schema for a Pentecost homily. The patristic quotes can be used either verbatim, or as the impetus for further reflection and homiletic development that would in turn need to be expressed by means of appropriate illustrations, stories, images, or examples. The citations given below respond to each of the readings assigned to the solemnity of Pentecost (in honor of the Year of the Holy Spirit). Note that much more material than can be included in one homily is provided; a selection and synthesis must be made.

SAMPLE HOMILY OUTLINE FOR PENTECOST

(Acts 2:1-11; Ps 104: 1, 24, 29-30, 31, 34; 1 Cor 12:3-7, 12-13; Jn 20:19-23)

PREMISE: In our acts of personal forgiveness, God makes visible the power of the invisible

Person of the Holy Spirit; we know the Holy Spirit when we are devoted to forgiveness.

Point #1: Life in the Spirit means accepting the divine gift of forgiveness.

- Sin impairs the image of God in us – St. Gregory of Nyssa: “Because of sin, each person’s spirit is a broken mirror which, rather than reflecting God, reflects the image of shapeless matter.”

- We require something greater than ourselves to overcome our sin – St. Diadochos of Photiki: “Only the Holy Spirit can purify the intellect, for unless a greater power comes and overthrows the despoiler, what he has taken captive will never be set free.”

- Jesus’ breathing on the apostles is a kind of re-creation: “You send forth your Spirit, they are created…”

- In re-creating us, the Holy Spirit gives us a share in his divine power – St. Thomas Aquinas: “This is exactly when the Holy Spirit works. He interiorly perfects our spirit, communicating to it a new dynamism so that it refrains from evil for love….In this way it is free, not in the sense that it is not subject to the divine law; it is free because its interior dynamism makes it do what divine law prescribes.”

- By our sharing in the redemption, we reveal to others the life of the Spirit – St. John Chrysostom: “Through the gift of the Holy Spirit we have been changed from men into angels, those among us who cooperate with his grace:…while remaining in the nature of men we show forth a manner of life that is worthy of angels.” When we live the dynamism of forgiveness, the privileges of the Spirit become our own – St. Augustine: “If we keep to the end what we have received, what the Holy Spirit has we also shall have; wherein nothing of ourselves shall war within us, and nothing shall be hidden in us from one another.”

Point #2 – Life in the Spirit means extending forgiveness to people in their hurts and fears.

- “Jesus came and stood before them” – relate to Jn 7:37-39: “Jesus stood up and cried out: ‘If anyone thirsts, let him come to me;’…Here he was referring to the Spirit.” Therefore, those thirsting for God’s mercy find it—and the Holy Spirit—as we stand before them offering forgiveness.

- As the apostles were hidden in the upper room, people try to hide in their sins – St. Gregory the Great: “It is true of every sinner that when he hides his sin within his conscience, it lies concealed within, secreted in his heart. The dead man comes forth when the sinner voluntarily confesses his acts of wickedness. The Lord told Lazarus, ‘Come forth,’ as if he were telling everyone dead in sin, ‘Why are you hiding your guilt within your conscience? Come forth now by confession, you who are lying concealed within yourself by your act of denial.’ Let the dead person come forth, then; let the sinner confess his sin.” (Note the marvelous parallel between Lazarus coming forth from the tomb and Christ coming into the locked “tomb” of the upper room in Resurrection, beckoning his disciples to “come forth” from the death of sin.)

- The Holy Spirit provides the grace to confront our sinfulness and that of others – St. Leo the Great: “Nor can he ever attain to the remedy of forgiveness who no longer has an Advocate (Paraclete) to intercede for him. For it is through him we call upon the Father; from him come the tears of repentance, from him the groans of those who kneel in supplication.”

- Jesus uses our fear to convince us about the compassion of the Spirit – Venerable Bede: “The apostles assembled with doors shut through that same fear which had scattered them; in this is shown the infirmity of the apostles. Jesus came in the evening because they would be most afraid at that time.” (Therefore, in the same way we manifest the Holy Spirit when we reach out to people mercifully in the depth of their fears.)

- We are most receptive of the Spirit when we are most detached – St. Basil: “The Spirit is not united to the soul by drawing near to it in place, but through the withdrawal of the passions.”

- The peace of the Spirit comes through our sharing in the wounds of Christ – St. John Chrysostom: “In showing them his wounds, Christ shows the efficacy of the cross, by which he undoes all evil things and gives all good things, which is peace.”

- The Spirit’s peace is the very source of forgiveness – St. Gregory the Great: “You see how they not only acquire peace of mind concerning themselves, but even receive the power of releasing others from their bonds.”

- The Spirit’s forgiveness transforms betrayal into friendship – St. John Chrysostom: “See how the Spirit wipes away all this iniquity, and uplifts to the highest dignity those who before had been betrayed by their own sins.”

Point #3 – Life in the Spirit means speaking the common language of mercy as our God-given

mission.

- “To each person the manifestation of the Spirit is given” through our active forgiveness.

- The “bold proclamations” and the “speaking about the marvels of God” = the Good News! (CCC 1847: “The Gospel is the revelation in Jesus Christ of God’s mercy to sinners.”)

- The love of the Spirit calms the Tower of Babel of life – St. John Chyrsostom: “Where there is charity the worst faults come to nothing; where there is charity the unruly thoughts of the mind come to an end.”

- The fire of the Spirit’s charity fills us with the desire to live for God – St. Gregory the Great: “Fittingly did the Spirit appear in fire; because in every heart that he enters into he drives out the torpor of coldness, and kindles there the desire of his own eternity.”

- The Spirit’s fire enkindles in us a healthy sense of sin – St. Gregory the Great: “The Spirit came in fire above men…because we should through zeal for justice search out our own sins…and consume them in the fire of penance.”

- The fire of forgiveness purifies and perfects us – St. Ambrose: “This is a fire which, as with gold, makes what is good better, and devours sin as stubble.”

- Through the goodness of our forgiveness, others come to know the Holy Spirit in us – St. Basil: “The Holy Spirit is by nature inaccessible, yet he yields to goodness.”

A Selected Bibliography of Patristic Preaching Resources

Two superb patristic resources remain staples for every preacher’s library have recently been reprinted. The first is Catena Aurea: Commentary on the Four Gospels Collected out of the Works of the Fathers, compiled by St. Thomas Aquinas. It is published in seven volumes by Preserving Christian Publications (Albany, New York, 1995).

The second is The Sunday Sermons of the Great Fathers, edited by M.F. Toal. It is published in four volumes by Preservation Press (Swedesboro, New Jersey, 1996). For the computer savvy, the Eerdmans reprint of the Edinburgh edition of The Early Church Fathers is now offered on CD-ROM by Logos Research Systems, Inc. (available through Paulist Press).

Preachers can look forward to two extremely promising imminent resources. One is Medieval Exegesis, Volume I by Henri De Lubac, translated by Mark Sebanc, to be published April 1, 1998 by Wm. B. Eerdmans. The second is also published by Eerdmans—a monumental multi-volume a series of biblical commentaries based on the Fathers of the Church entitled The Church’s Bible. The project, edited by Professor Robert Wilken, aims to put in print commentaries that will promote biblical books central to Christian faith and life, namely, John, Matthew, Romans, 1 Corinthians, Isaiah, Genesis, Psalms, and Song of Songs. The first volume is due to be released in 2000.

In addition, the following patristic resources are extremely helpful for preaching:

• Barnecut, Edith (Ed.). Journey with the Fathers: Commentaries on the Sunday Gospels, 3 volumes. Hyde Park: New City Press, 1994.

• Gregory of Nyssa, St. From Glory to Glory. Crestwood: St. Vladimir’s Press, 1995.

• Gregory the Great, St. Forty Gospel Homilies. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1990.

• Jurgens, William A. (Ed.). The Faith of the Early Fathers, 3 Volumes. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1970, 1979.

• Leo the Great, St. Sermons. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1996.

• Palmer, G.E.H., Sherrard, Philip, Ware, Kallistos (Trans.). The Philokalia, 4 volumes. London: Faber and Faber, 1979, 1981, 1984, 1995.

• Romanos, St. On the Life of Christ. New York: HarperCollins, 1995.

• Russell, Claire (Ed.). Glimpses of the Church Fathers. London: Scepter, 1994.

• Spidlik, Thomas. Drinking from the Hidden Fountain: Cistercian Publications, 1994.

• Wiles, Maurice & Santer, Mark (Eds.). Documents in Early Christian Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975. A Patristic Breviary. Kalamazoo:10

The last word goes to St. Augustine, one of the greatest Fathers of the Church, on the Fathers of the Church:

They have transmitted to us all that they have received. They have taught to the Church what they have learned within the Church. All that they found in the Church, they kept; that which they learned, they taught. That which they have received from the Fathers, they have transmitted to the sons.”