by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

Each year the Church’s Lenten reading of Genesis reaches its climax, just on the verge of Holy Week, with the story of Joseph’s reconciliation with his brothers.

Each year the Church’s Lenten reading of Genesis reaches its climax, just on the verge of Holy Week, with the story of Joseph’s reconciliation with his brothers.

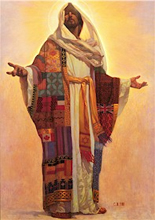

The liturgical chants relevant to that story suggest why: the story of Joseph is taken as a prefiguring analogue, or typos, of the events of Holy Week and Pascha. To sum them up, Joseph was the beloved of his father, sold for a price by his brothers, unjustly accused and imprisoned on false testimony, enduring all with patience, and, finally, forgiving his oppressors.

Joseph’s story thus adumbrates the dramatic days of Holy Week; his reunion with Jacob, furthermore, foreshadows Jesus’ Paschal restoration to the One who sent him:

“I ascend to my Father” (John 20:17).

Joseph’s significance in the History of Salvation, nonetheless, consists in more than these points of correspondence with the Gospel narratives, because his place at the end of the Lenten season brings closure to themes—and resolution to conflicts—introduced at the beginning of that season. Without Joseph, Genesis would be a completely different book. His story looks back and ties everything together. Joseph looks forward to Christ by looking backward to the whole of Genesis.

For instance, we begin Lent with the account of man’s God-given rule over the land:

“Be fruitful and multiply; fill the land (ha’aretz) and subdue it; have dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over every living thing that moves on the land (ha’aretz)” (Genesis 1:28).

Then, at the end of Genesis, Joseph appears in history as

“the man, the lord of the land, (ha’ish ‘adone ha’aretz)” (42:30).

Joseph is filled with the same “Spirit of God” (ruach ‘Elohim) that first hovered over Creation (1:2; 41:28).

Because of Joseph’s wise rule, Egypt becomes a fruitful place—nearly an Eden—to which come people from “all the land” (col ha’aretz) to be fed (41:57; cf. 41:54). Under Joseph’s rule,

“the land (ha’aretz) brought forth abundantly” (41:47).

This scene in Egypt picks up the theme of abundance early in Genesis:

“And the land (ha’aretz) brought forth grass, the seed-yielding herb according to its kind, and the fruit-yielding tree-its seed in itself-according to its kind. And God saw that it was good” (1:12).

Given the Holy Week context of the Atonement, there is a special significance in Joseph’s forgiveness of—and reconciliation with—his offending brothers. The crime of fratricide, early introduced in Genesis by Cain and extended through the vengeful mindset of Lamech, is overturned in the action of Joseph. Generations of fraternal contention are put right when wise Joseph, superceding Babel’s confusion of the tongues, suddenly breaks from Egyptian into Hebrew to exclaim,

‘ani Yoseph ‘achikem—“I am Joseph your brother” (45:4).

In the full contextual narrative of Genesis, his words of forgiveness and comfort serve to amend the struggle between Ishmael and Isaac, and to soften Esau’s urge to murder Jacob. The fraternity of man is restored in the soul of Joseph.

It is not completely accurate to say that true fraternity is restored in Joseph, however, for the simple reason that in Genesis there never was any true fraternity; the sentiment and claims of brotherhood were violated from the beginning (4:8). So Joseph’s brothers, when they threw him into the pit, were simply carrying on the lethal tradition that had corrupted fraternity from the start.

Until Joseph, the Bible paints a landscape in which

“every intent of the thoughts of [man’s] heart was only evil (ra’ah) continually” (6:5).

Indeed, with respect to his brothers, Joseph declared,

“you meant evil (ra’ah) against me” (50:20).

He, however, does not retaliate, thus breaking the evil cycle. Why does he not retaliate? Genesis provides a hint: It is significant that immediately after identifying himself to his brothers Joseph inquires about Jacob:

“Is my father still alive?”

This is Joseph’s dominating concern: his father. What he does in this dramatic, redemptive scene, Joseph does with his father in mind. What he seeks, for himself and for his brothers, is reunion with the father. For Joseph, there is no true brotherhood except with this true fatherhood.

Joseph, then, emerges in Holy Scripture a living prophecy of Christ, inasmuch as he introduces into Salvation History the first example of thorough, unselfish forgiveness. He foreshadows the Atonement wrought by Christ, because he finds it in his heart to forgive his brothers for the sake of his father. To honor his father, Joseph makes himself—anew—brother to those who had rejected the claims of brotherhood.