by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

Once again, Fr. Patrick hits it out of the park.

The special soteriological significance of various Old Testament figures has long been recognized. In the second century, for instance, Melito, the bishop of Sardis, wrote:

“Surely, in the patriarchs, in the prophets, and in the whole people of God, the Lord prearranged his own sufferings, giving them warrant through the law and the prophets. For that which was to exist in a new and greater fashion was pre-planned long in advance, in order that when it should come into existence one might attain to faith, simply because it had been predicted long in advance. So indeed also the suffering of the Lord, predicted long in advance by means of types-and today seen-has brought about faith, precisely because it has occurred just as it was foretold. And yet men have understood it as something completely new.”

In addition to this apologetic value, Melito commented, these Old Testament typoi carry a special relevance for Christian theology—the reflective understanding of the Revelation received in faith. Christ’s connection with the earlier biblical figures is both theological and historical. Indeed, it is the one because it is the other, inasmuch as Divine Revelation is inseparable from the revelatory events and the Scriptures-also revelatory-which record and interpret those events. Thus, writes Melito,

“The truth is, the mystery of the Lord is both old and new-old insofar as it involved the type but new insofar as it concerns grace. And what is more, if you pay close attention to the type, you will see the reality through its fulfillment.”

Melito then proceeds to mention some of these typoi of the Lord’ Passion:

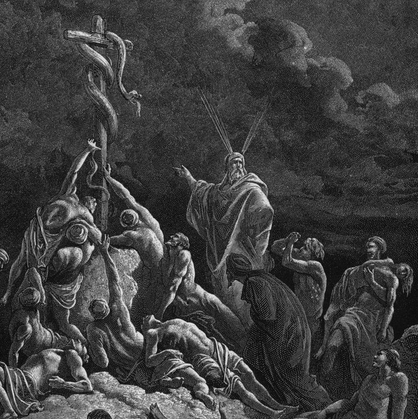

“Therefore, if you desire to see the mystery of the Lord, give close regard to Abel who likewise was put to death, to Isaac who likewise was bound hand and foot, to Joseph who likewise was sold, to Moses who likewise suffered exposure, to David who likewise was hunted down, to the prophets who likewise suffered because they were the Lord’s anointed.”

Who, after all, really was that Paschal Lamb slain the land of Israel’s captivity? Melito knows:

“Pay close attention also to the one who was sacrificed as a sheep in the land of Egypt, to the one who smote Egypt and who saved Israel by his blood” (Paschal Homily 4).

In regard to the Old Testament types, permit me to whisper a word of caution. Theological interest in this subject is not to be identified with what is called typology. During the past century or so many theologians and exegetes have taken a pattern of typology from modern literary study and have adapted it to the biblical studies. I believe this adaptation is less than felicitous.

The approach of typology, an analytical pattern that began in the sciences, was borrowed and modified by men of letters for the interpretation of literature. It was believed that this adaptation added to literary studies a new heuristic tool, and the adaptation was part of a more general movement, some decades ago, to impose on the humane disciplines, including literature and behavioral studies, the culturally more-respected standards of scientific objectivity. It was part of the objectification and quantification of the academic curriculum.

While I venture no opinion on the success of typology’s move from science to literature, I do query the value of its further migration into Sacred Theology. My doubt on this point is twofold:

First, the “types” discernible in the Bible are not literary types. They are concrete historical persons, events, and institutions. They appear in Holy Scripture because they appeared in a specific history, and that specific history—not just its literary expression—is what ties them to Christ. For this reason, typology is, at best, a distraction when applied to Holy Scripture.

It may be argued that the Bible, insofar as its material is historiographical, is a proper object for any legitimate tool of literary investigation. I do not agree in this case. The Bible is not a work of historiography independent of its history; it is a formal component of that history. It is both a product of that history and a further stimulant of that history. For this reason a measure of caution is required, lest the literary study of Holy Scripture be abstracted from the specific history of which it is an essential part.

Second, modern biblical “typologists” (I apologize for the word, but it will have to do) imagine themselves to be following the footsteps of the Church Fathers in drawing attention to Old Testament types. This is not the case, however. If it were the case, we would expect at least one or two Church Fathers to have used the expression “typology.”

They didn’t . . . ever. Five minutes’ attention to either Lampe’s Greek lexicon or Du Cange’s Latin lexicon suffices to show the Church Fathers’ complete unfamiliarity with the term typologia.

Patristic interest in the Old Testament “types” did not regard them simply as figurative analogues to persons, events, and institutions in the New Testament. The Fathers knew that the Old Testament types cannot be abstracted from the continuous historical structure of Revelation. The relationship of these types to Christ involved no merely artistic, trans-historical polarity; they were woven into the same historical fabric as the Messiah himself. The presence of biblical types is simply a particular display or form of prophecy

Moreover, the isolation of biblical types—their insertion into the alien discipline of “typology”—can leave the impression, as it often does, that only certain parts of the Old Testament are pertinent to the interest of Christian Theology.

The modern disposition to treat the Old Testament typoi under the non-biblical and non-traditional category of “typology” is a symptom, I believe, of a deeper hermeneutical misunderstanding. It is part of the contemporary habit of separating the two Testaments into discrete literary bodies, so that, in the course of studying these two Testaments, the reader discerns that figures in the one are analogous to figures in the other; the polar relationships between the two is the stuff of “typology.”

Let me mention that this approach, from the perspective of Christian Theology, is just plain wrong.

In the New Testament and the writings of the Church Fathers, the Old and New Testaments testify to, and are part of, one continuous and integral history, in which God reveals Himself to man and redeems the world. Biblical “types” are integral to, and inseparable from, the history and the historiography of Revelation.

No part of the Old Testament can be singled out from the rest and be labeled “messianic.” All the Old Testament is messianic. It is all prophetic. It all pertains to God’s anointed One.