by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

Augustine’s Mistake (or we could say ‘Calvin’s Confusion’) is one of the deepest and most tragic blunders in the history of theology.

Toward the end of a long reflection on the Holy Spirit—Romans 8—the Apostle Paul introduces the theme of Divine Providence, the profoundly mysterious influence God brings to bear on the direction of history.

A textual problem attends this introduction (8:28); it has to do with the word “God.” Depending on which manuscripts are followed (and sheer antiquity is not an adequate guide here, because the manuscripts come from Christian churches of great antiquity, and some of the textural variants must have been introduced very early), the meaning of the passage is either

“in everything God works for good with those who love Him,”

or

“God makes everything work together for the good of those who love Him,”

or

“everything works together for the good of those who love God.”

Notwithstanding their differences, each of these readings testifies to God’s providential guidance of the lives of those who love Him.

Having introduced the theme of Divine Providence, Paul continues it through the rest of this chapter, and then, in chapters 9—11, he applies it directly to a disconcerting historical dilemma posed to the minds of the early Christians; namely, the rejection of the Gospel by masses of the Jewish people, not only by the Temple leaders in Jerusalem but also by many synagogues in the Diaspora. How, thinking Christians wondered, could this have happened? If God had taken such great care of the children of Israel for nearly two thousand years, how did so many of them fail to recognize the Messiah? Was this not a breakdown in Salvation History?

No, writes Paul, the defection on the part of the Jews was permitted by God because He had in mind some greater benefit that would ensue. He is the Lord of history; He knows everything ahead of time. And, knowing everything ahead of time, He quietly and mysteriously arranges and prearranges the circumstances of history in order to bring about His greater blessings.

Paul appeals the ancient theme of God’s ability to bring good out of evil. His thesis, which forms the substance of the argument in Romans 9—11, is drawn from the Old Testament. It is obvious, for instance, in the account of Joseph—elect among Jacob’s sons—the man whose trust in the divine guidance permits him to tell his betraying brothers,

“As for you, you meant evil against me; God, however, intended something good, in order to bring it about what we have today—to preserve the lives of many people” (Genesis 50:20).

When God chose Joseph to be the savior of his family, He also permitted the other brothers’ betrayal; indeed, their betrayal became part of the drama of the family’s deliverance. The fabric of the story would be incomplete without the threads of evil woven into it.

What, then, does Holy Scripture mean when it asserts that God “predestines”? The verb, proorizo, means “to arrange ahead of time. In the biblical context, where this verb appears with “foreknow” (proginosko, “to know ahead of time”), it signifies the providential arrangements by which God leads people to the grace of the Gospel. That is to say, predestination embraces the mysterious influences that God brings to bear on history, so that all things work together for the good of those who love Him.

The verb “predestine”—the noun never appears in the Bible—has no reference to an alleged divine decree whereby some people are consigned to heavenly life and others to everlasting damnation. On the contrary, God wills all men to be saved. Indeed, in the Bible, predestination does not refer to a divine decree at all. It is a description, rather, of God’s providential activity in history, working to bring good out of evil.

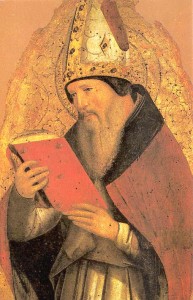

Nowhere, therefore, does Holy Scripture hint even faintly at a person’s “predestination to hell.” In fact, this repulsive idea does violence to the Bible, in which predestination is always a category of grace, never of punishment. Predestination pertains invariably to the divine call, not the rejection of that call. It is always a description of the divine favor, not of disfavor. Saint Augustine’s misunderstanding of this point must be counted, I think, among the deepest tragedies in the history of theology.

In His providential guidance of history, God makes use of man’s sins. He never “prearranges” those sins nor wills those sins; He does not, that is to say, predestine men to sin. Even less does God predestine anyone’s damnation. Damnation was never God’s idea, and the majestic sovereignty of God receives no glory from anyone’s eternal loss.

The foreknowledge and predestination of God is Paul’s way of describing the priority of divine grace in redemption and justification. The initiative is God’s, not ours. We foreknew nothing; we prearranged nothing. God has done it all. He knows and He determines, ahead of time, what form His work in history (including the history of each of us) will take. God manages, as in the case of Joseph’s brothers, to use even man’s sin to advance the cause of divine grace.

Those who truly experience His grace are aware of themselves as known by God (1 Corinthians 8:3; 13:12), loved by God (1 John 4:19), chosen by God. When he speaks of predestination, Paul is describing the experience of life in the Christian Church.

That is to say, the sense of predestination is an existential perception. It pertains to spiritual experience.