by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

Holy Saturday bears two aspects with respect to Jesus, corresponding to the two “places” in which he is to be found. The earthly aspect the day is visible, at least in the sense that Jesus’ immolated body now lies in the tomb. There is also an invisible aspect, inasmuch as Jesus’ soul has left that body and gone elsewhere.

According to the earthly and visible aspect of Holy Saturday we behold the Savior lying in the tomb, his labor over; tetelesthai, says the Gospel of John,

“it is completed!”

The eternal Son rests there now, on this seventh day, as he rested on the world’s first Sabbath, after the work of Creation was completed. No one actually sees the Savior there, once the stone is rolled to the door of the sepulcher and the government has officially set its seal to guarantee that no one disturbs his rest.

Jesus’ enemies, on this occasion, fear that the tomb may be disturbed by forces from without, whereas the real danger to the integrity of that grave comes from the dead man who lies buried there.

“Make it as secure as you know how,”

Pilate directs the guardians of the tomb—perhaps the most ironical injunction ever given.

The second and truly invisible aspect of Holy Saturday is what happens to the soul of Jesus while his body lies in the tomb. Right away I regret putting the matter this way. Indeed, this way of posing the question—“What happens to Jesus’ soul?”—will almost certainly lead to the wrong answer. Nothing really happens to Jesus, for the simple reason that he is no longer a passive being. Death has no hold on him.

In fact, the creeds and ancient sources use the active voice when dealing with this subject; we are told that Jesus

“descended first into the lower parts of the earth” (Ephesians 4:9)

and

“he went and preached unto the spirits in prison” (1 Peter 3:19).

Although his body lies helpless in the hands of those who bury him, no one controls his soul. Jesus can go wherever he wants. He is, according to the Vulgate text of Psalm 87, inter mortuos liber,

“free among the dead.”

Jesus chooses to go someplace where other dead people have no choice but to be there. He goes to a place known in Hebrew as Sheol, translated into Greek as Hades and into Latin as inferna. Perhaps the closest English equivalent is “the nether world” or “the lower regions.” It is the realm of the dead. Descendit ad inferos, says the Apostles Creed,

“he descended to the dead.”

The Savior chooses to pay a visit to that mysterious place, to take care of what he regards as unfinished business.

Because Jesus’ descent into the nether world occurs between his earthly life and his new status as a

“life-giving spirit” (1 Corinthians 15:45),

Holy Saturday receives its shape from both Good Friday and the feast of Pascha. In theory, whether it is linked more closely to one or the other should make no difference.

In practice, however, this has not always been the case. Certain modern theologians, linking Holy Saturday closely to Christ’s death, tend to regard his descent into the nether world as an extension of the Cross; they regard this descent as tragic. Since Christ’s passage into the realm of the dead manifestly pertains to his death, these theologians describe his experience of that passage in terms of ongoing and almost unimaginable dereliction. Hades becomes Valhalla.

The theologians following this view argue that Christ, when he died, was reduced to a passive state. He entered the nether world as victim. He tasted a second death; he experienced, on dying, a radical alienation from the Father. He became, indeed, the concentrated object of the Father’s wrath, as though guilty of all the sins ever committed. According to this view, Christ suffered the experience of damnation; it was no rhetorical impulse, therefore, that prompted him to inquire of the Father,

“Why hast Thou forsaken me?”

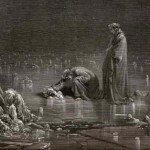

An opposing and more ancient perspective on Holy Saturday links Christ’s descent into the realm of the dead more closely with his Resurrection than with his suffering on the Cross. According to this older view, which utterly pervades the traditional Christian sources-Holy Scripture, imagery abundantly attested in the Church’s hymnography and art, classical catechetical material, and patristic writings-Christ went triumphantly into the realm of death, trampling down death by death.

He was not a victim but a conqueror

Christ was not the least bit passive in this descent. In his divine Person and human soul he penetrated the region of darkness with the abundance of his unconquered light, shattering the bars of Sheol, and liberating those ancients who in faith awaited his arrival. No victim, he—not now, not here. He arrives, rather, in utter majesty.

When, on Sunday, he would rise from the dead, Christ had already invaded the house of the strong man armed, had despoiled him, and had left his realm in ruins. Dante’s Vergil (in Longfellow’s translation) describes the event of Christ’s arrival in the nether world

“I saw hither come a Mighty One, / With sign of victory incoronate.”