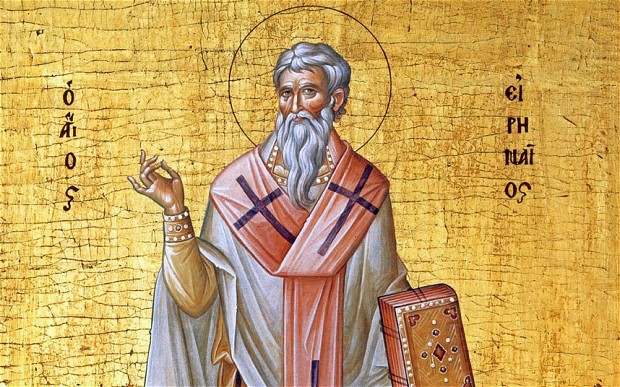

St. Ireneaus of Lyon, terror of gnostics, crusher of heresy

by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

In the second century, Irenaeus, the second bishop of Lyons, explicitly asked-with respect to the eternal Word –

“for what purpose did he come down?” ( Against the Heresies 2.14.7).

And the answer:

“that he might destroy sin, abolish death, and give life to man” (3.18.7).

Irenaeus explains,

“God created man that he might live. If man, then, having lost life through the injury inflicted by the corrupting devil, did not recover life but was completely abandoned to death, God would have been defeated, and the wickedness of the serpent would have prevailed over God’s intent.

Inasmuch, however, as God is both invincible and gracious, He demonstrated His graciousness in correcting man and vindicating all men (as I mentioned before), by using the Second Man to ‘bind the strong man and despoil his goods.’

Thereby He destroyed death, restoring life to man, who had become subject to death. For Adam had become the property of the devil, and the devil held sway over him by maliciously deceiving him with a promise of immortality and thereby making him subject to death” (3.23.1).

As in the Epistle to the Hebrews, these enemies—sin, death, and the devil—are inseparable in the mind of Irenaeus. For him, consequently, the Incarnation and the Atonement are also inseparable. He writes,

“the very hand that formed us in the beginning and shapes us in our mother’s womb, came to seek us in these latter days, when we were lost, laying hold on his lost sheep and placing it on his shoulders and joyfully restoring it to the sheepfold of life” (5.15.2).

Closely following Genesis 3 and the theology of the Apostle Paul, Irenaeus declines to separate sin, death, and demonic servitude. However they may differ conceptually, these three enemies of man are organically joined and existentially identical. Sin is not just a moral failing or an offense to the divine honor; sin is the introduction of corruption and demonic slavery into man’s entire being in the Cosmos.

In making this point, Irenaeus had in mind to refute Marcion and the second century Gnostics, according to whom evil pertained only to man’s lower, material nature. No, responded the Bishop of Lyons, sin involves man’s entire being, inasmuch as it places human existence in bondage to the devil and to the corruption of death. Death does not affect just to man’s body but his entire being.

Apart from Christ, Irenaeus saw, death is eternal. Apart from Christ, death is hopeless. Death is the supreme alienation from God, inasmuch as

“the nether world does not bless You, / death cannot praise you, / and those who descend can never expect Your fidelity” (Isaiah 38:18).

Irenaeus explained,

“we are not all the sons of God: those only are so who believe in Him and do His will. And those who do not believe, and do not obey His will are sons and angels of the devil, because they do the works of the devil. . . . For as, among men, those sons who disobey their fathers, being disinherited, are still their sons in the course of nature, but by law they are disinherited and do not become the heirs of their natural parents; so in the same way is it with God: those who do not obey Him, being disinherited by Him, have ceased to be His sons (Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching 31).

Furthermore, according to Irenaeus, the Word’s assumption of the flesh was required for our salvation because Adam’s sin had been committed in the flesh. Sin in the flesh required salvation in the flesh. Irenaeus explained,

“So the Word was made flesh in order that sin, destroyed by means of that same flesh through which it had gained mastery and taken hold and lorded over it, should no longer be in us.”

And, again,

“that so he might join battle on behalf of our forefathers and vanquish through an Adam what had stricken us through an Adam.”

Irenaeus here is clearly the heir to St. Paul, who had already contrasted Christ and Adam in terms of “disobedience unto death” and “obedience unto life” (Romans 5:12-19).

In his treatment of Salvation, however, Irenaeus stresses the Resurrection much more explicitly than is obvious in the Epistle to the Hebrews, and this emphasis, in turn, contours his approach to the Incarnation. Thus, Irenaeus writes of our Lord’s birth, which the Word of God underwent for our sake, to be made flesh, that he might reveal the resurrection of the flesh and take the lead of all in heaven.

In this way, explains Irenaeus, Christ becomes

“the first-born of the dead, the head and source of the life unto God” (39).

In his development of this idea, as well, Irenaeus is still following the lead of St. Paul, who contrasted Christ and Adam with respect to death and Resurrection (1 Corinthians 15:22,45).

In tying the soteriological intent of the Incarnation to the Lord’s Resurrection from the dead, Irenaeus advances an important doctrinal perspective: The work of Salvation is completed by the glorification of Christ.

Thus, Irenaeus, not neglecting the biblical theme of “obedience in the flesh,” sets himself to provide a more ample answer to the question “Why Incarnation?” His larger answer to this question, an answer that includes the Lord’s Resurrection, colors his Soteriology with a dominant concern for the total transformation of humanity—and all of Creation—in Christ. This became a major theme by which Irenaeus refuted the cosmic dualism of the Gnostics.

In this respect, Irenaeus was one of our earliest “biblical theologians,” in the sense that he formed a biblical synthesis—mostly from Paul and the Epistle to the Hebrews—in order to address the philosophical questions and religious controversies of his day.

He serves as a model for the ministry in which Christian thinkers, in every age, are called upon to serve.