by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

Saint John’s early affirmation,

“The Word became flesh,”

is both the thesis of his whole gospel and the interpretive principle for understanding its sundry parts. This one verse affirms that everything expressed in the divine Word took on a fleshly, human form. In the stories recounted by John, we ponder divine Wisdom translated into human discernment, the eternal purpose enacted as a historical drama, and infinite love assuming the shapes of personal friendship, affection, and familial endearment.

Everything in the Word becomes flesh. The infinite kindness of God is configured in the provision of wine at a wedding feast and the gift of bread for a crowd of thousands. Like the Word quietly taking flesh in the virgin’s womb, the mysterious wine and the enigmatic bread are inserted into—and alter—the experience of human beings. In each case the Word is made flesh and dwells among men.

Thus, the thesis, “God so loved the world,” assumes the form of an infant loved by His mother and learning, in turn, to love her. He learns it well. Later in His life another man was so aware of the friendship of Christ that he commonly referred to himself as “the disciple whom Jesus loved.”

The Word’s loving devotion to His mother and His affection for His friend—both expressions of the Incarnation—came together when, hanging on the Cross, Jesus

“saw His mother and the disciple whom He loved standing by.”

The mother was on the point of losing her son, and the disciple his best friend. Loving them both—each in a distinctive way—Jesus gave this older woman and this younger man to one another as His parting gift:

“Ma’am, behold your son . . . Behold you mother.”

Jesus’ love for Mary and John, seizing the occasion of their common heartbreak, bound them to one another through the love each of them had for Him. Here on Calvary, that is to say—and with overwhelming emphasis—

“The Word was made flesh”;

God’s infinite love assumed the human affections of a new family, when “the disciple took her to his own.

An explicit and heightened emphasis on the friendships of Jesus is one of the special features of John’s work. John the Baptist called himself Jesus’ “friend,” philos (3:29). Jesus spoke to the disciples of

“Lazarus, our friend”—ho philos hemon (11:11).

To the disciples themselves He said,

“No longer do I call you servants . . . but I have called you friends (philous) (15:15).

These friends He described as “His own,” declaring that the Good Shepherd

“calls His own (idia) sheep by name and leads them out. And when He brings out all His own (ta idia panta), He goes before them” (10:3-4).

And again,

“I know Mine, and Mine know Me” (10:14).

Indeed,

“having loved His own (tous idious) who were in the world, He loved them to the end” (13:1).

This “end” (telos) is achieved in Christ’s love for these friends:

“I am the Good Shepherd. The Good Shepherd gives His life for the sake of the sheep” (10:11).

In John, the love of Christians for one another is modeled on the love all of them come to know in Christ. Thus, whereas the mandate in the Synoptic Gospels is to love our neighbors as ourselves (cf. Mark 2:31 et al.), in John’s account we are to love one another more than ourselves. And the basis for this new mandate is not an ethical principle, but a personal example:

“I give you a new commandment, that you love one another. As I loved you, that you also love one another” (13:34).

A common translation of this verse conveys the motive for this love in the perfect tense:

“As I have loved you.”

This translation, I believe, dilutes the sense of the expression. In fact, John uses the aorist tense here,

“As I loved (egapesa) you.”

That is to say, his choice of tense indicates a concrete and specific act of love. John is thinking of the Cross, on which the Good Shepherd gave His life for the sake of the sheep:

“Greater love than this has no one, that someone should give his life for the sake of his friends” (15:13).

John speaks elsewhere of the love modeled on the Lord’s voluntary death:

“In this have we known love, because that Man (Ekeinos) gave His life for our sakes. And we ought to give our lives for the sake of the brethren” (1 John 3:16).

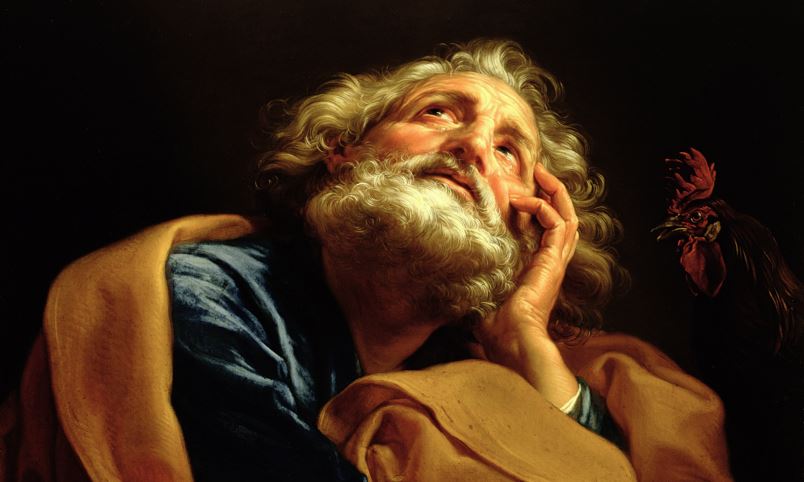

This was the love to which the Apostle Peter aspired:

“Lord, why can I not follow you now? I will give my life for Your sake” (13:37).

Such love, nonetheless, surpasses human power. Of his mere volition, Peter was not able to do it. It wasn’t possible, because He did not have, as yet, the model of Christ. God’s own gift is prior:

“In this is love, not that we have loved God [perfect tense: egapekamen], but that He loved us [aorist tense: egapesen]” (1 John 4:10).

Once Peter has received this love as Christ’s gift, however, he will be able to lay down his life for Christ’s sake:

“’When you have grown old, you will stretch out your hands, and someone else will tie you and bear you where you do not wish.’ He said this, signifying by what death he would glorify God. Saying this, He spoke to him, ‘Follow Me!’” (John 21:18-19).

Peter will be able to display this love only as an act of “following.”