by Robert Arakaki

The Lost World Scenario

An alternative scenario can be found in another book written by Michael Crichton, The Lost World.

“No, no,” Levine said earnestly. “I’m quite serious. What if the dinosaurs did not become extinct? What if they still exist? Somewhere in an isolated spot on the planet.” (Lost World p. 5)

The Protestant view of history assumes that there once was an apostolic Church but itno longer exists today. But Protestants and Evangelicals need to ask the question:What if the apostolic Church still exists today? What if there was a church where the errors of the papacy were avoided? What if that church was within driving distance today?

For Evangelicals Eastern Orthodoxy is a Lost World. Many Protestants and Evangelicals drive by these funny looking ethnic churches with strange names unaware of these churches’ connection to the early Church. The estrangement of the Great Schism of 1054 resulted in Western Christians, both Roman Catholics and Protestants, not being aware of Orthodoxy’s existence and its distinctive approach to doctrine and worship. The Protestant Reformers’ bitter struggle against medieval Catholicism gave Protestants a severe astigmatism that skewed their understanding of church history. Protestants came to view the early Church through the prism of Catholicism imagining the Apostolic Church to be part a lost past. But while the Protestants of the 1500s can be excused for having a distorted perspective on church history, the situation is quite different today. Many Protestants in recent years are learning about the early church fathers and are having a firsthand encounter with Orthodoxy.

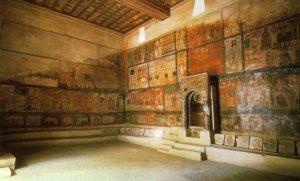

This is why the first visit to an Orthodox Church is often such a surprise for many Evangelicals. Orthodoxy represents what many Protestants are seeking after, the early Church before Roman Catholicism. The Orthodox Liturgy is part of living tradition that goes back to the days of the Apostles. At first glance many would find this hard to accept especially the icons, the elaborate liturgical ceremonies, and ornate vestments worn by priests. All these are so radically different from the austere minimalism that mark Reformed, and especially, Puritan worship, or the exuberant expressiveness of charismatic worship.

But when approached from the standpoint of the Old Testament pattern of worship transformed by the New Covenant of Jesus Christ, the Divine Liturgy makes perfectly good sense. The vestments worn by Orthodox priests are patterned after those worn by the Old Testament priests.

If Jesus Christ is the Passover Lamb who takes away the sins of the world then it makes sense to view the Eucharist as the culmination of the Old Testament sacrificial system. A careful reading shows that icons have a biblical basis in the Old Testament (Exodus 26, 2 Chronicles 3). Recent archaeological findings have shown that early Jewish synagogues had images on their walls.

All this explains why a conscientious re-reading of Scripture and an open minded study of church history have led thousands of Protestants: pastors, professors, devout laymen to the conclusion that the Orthodox Church is indeed what it claims to be: the very Church founded by Christ himself, not some later knock off imitation. Visit Journey to Orthodoxy.com

Testing the Lost World Hypothesis

Protestant ecclesiology assumes a major discontinuity in history. Protestant church history is based on the idea that there once was a pure and apostolic Church but that early Church fell into spiritual darkness. It was not until the Reformation that Martin Luther recovered the Gospel and spiritual light returned to Europe. Protestants believe that using the principle of the “Bible alone” they will be able to reform (reconstruct) the Church as it was meant to be. These assumptions are foundational to defining Protestant identity. The Protestant view of history is crucial for explaining why Protestants are different from Roman Catholics (they follow the ‘Bible alone’) and why they remain separate from Roman Catholics (they have Gospel in the pure form of justification by ‘faith alone’).

Orthodoxy presents a significant challenge to the Protestant paradigm of church history. It is the Lost World that did not become extinct. Orthodoxy claims a historical continuity that goes back to the first century but it looks so different from what Evangelicals imagine the early Church to have been like. Evangelicals can test Orthodoxy’s claim to historical continuity by studying the church of Antioch.

Many Evangelicals greatly admire the Apostle Paul the great missionary but only a few know the name of his home church. Every missionary has a home church from which they were sent. According to Acts 13:1-3, Paul received his missionary calling at the church of Antioch. In this brief passage we learn during the Liturgy the Holy Spirit directed that Paul and Barnabas be set aside for missionary work. The Church of Antioch – the Apostle Paul’s home church — continues to exist to this day. The current Patriarch of Antioch,John X, can trace his apostolic succession back to the first century. The Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of North America, which received two thousand Evangelicals into Orthodoxy in 1987, has direct ties with the Apostle Paul’s home church. This is a spiritual lineage that any Evangelical would be proud to have!

Another way an Evangelical can test the Lost World hypothesis is by tracing the form of worship used in the church of Antioch. We learn from that same passage (Acts 13:1-3) that the worship in Antioch was liturgical worship. The Greek word for “worshiping the Lord” (NIV) or “ministered to the Lord” (KJV) is “leitourgounton” from which we get “liturgy.”

This is why Orthodox Christians refer to their Sunday worship as “the Liturgy.” The worship of the first Christians in Jerusalem was liturgical.

This can be seen in Acts 2:42 which referred to the Liturgy of the Word (the Apostles’ teaching) and the Liturgy of the Eucharist (the breaking of bread). On most Sundays we use the fifth century Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom and about ten times a year we use the fourth century Liturgy of St. Basil the Great. These liturgies which were inherited or passed on from the bishops before them are part of the Tradition of the ancient Church. In October we use the first centuryLiturgy of St. James. The liturgy was named after the Lord’s brother who served as bishop of Jerusalem and in that capacity presided over the first church council recorded in Acts 15. This historical continuity in Orthodox worship stands in stark contrast with the rapidly evolving forms of worship in Protestantism and Evangelicalism. The historic pattern of worship is pretty much lost in much of Evangelicalism. In the more progressive churches the order of worship changes from week to week depending on the decisions made by the praise and worship team. In the more ‘traditional’ Protestant churches the order of worship found in the back of the hymnal is never used by the congregation.

A third way an Evangelical can test the Lost World hypothesis is by tracing the form of church government. The early form of church government was episcopal – rule by bishop. Ignatius of Antioch, the third bishop of Antioch and a disciple of the Apostle John, wrote a series of letters on his way to martyrdom in Rome in 98 or 117 about the importance of obeying the bishop. In his letters he exhorted people not to celebrate the Eucharist (Lord’s Supper) apart from the bishop (Letter to the Smyrneans VIII and IX). All this is so different from Evangelicalism which favors congregational autonomy or the Presbyterian classis. Protestants may be averse to the episcopacy due to their opposition to the Roman Catholic Church but the fact remains that the episcopacy was the norm in the early Church. The notion of a universal papal supremacy was a distortion that Protestants rightly objected to. Orthodoxy also object on the basis that papal supremacy is contrary to Tradition.

This supports the Lost World hypothesis that the Orthodox Church is the same church as the early Church.