by St. John Cassian

As we start to speak of the institutes and rules of monasteries, where could we better begin, with God’s help, than with the very garb of the monks? After having exposed their outward appearance to view we shall then be able to discuss, in logical sequence, their inner worship.

As we start to speak of the institutes and rules of monasteries, where could we better begin, with God’s help, than with the very garb of the monks? After having exposed their outward appearance to view we shall then be able to discuss, in logical sequence, their inner worship.

And so, it is proper for a monk always to dress like a soldier of Christ, ever ready for battle, his loins girded.

The monk’s garment should only be such that it covers the body, countering the shame of nakedness, and prevents the cold from doing harm, not such that it nurtures seeds of vanity or pride. In the words of the same Apostle:

“having food and covering, let them be satisfied with these” (I Timothy 6:8).

He says “covering” and not “vesture,” which some Latin editions say incorrectly. This means only what may cover the body, not what may flatter it by its splendid style.

He says “covering” and not “vesture,” which some Latin editions say incorrectly. This means only what may cover the body, not what may flatter it by its splendid style.

Thus it should be commonplace, so as to be indistinguishable in terms of novelty of color and cut from what is worn by other men of this chosen orientation; in no respect should it be self-consciously meticulous, but neither, on the other hand, should it be grimy with filth accumulated by neglect; finally, it should be different from the apparel of this world in that it is kept completely in common for the use of the servants of God.

Thus it should be commonplace, so as to be indistinguishable in terms of novelty of color and cut from what is worn by other men of this chosen orientation; in no respect should it be self-consciously meticulous, but neither, on the other hand, should it be grimy with filth accumulated by neglect; finally, it should be different from the apparel of this world in that it is kept completely in common for the use of the servants of God.

There are some other things in the garb of the Egyptians that pertain not so much to the well-being of the body as to the regulation of behavior, so that the observance of simplicity and innocence may be maintained even in the very character of their clothing. Thus, day and night they always wear small hoods that extend to the neck and the shoulders and that only cover the head. In this way they are reminded to hold constantly to the innocence and simplicity of small children even by imitating their dress itself. Those who have returned to their infancy repeat to Christ at every moment with warmth and vigor:

“Lord, my heart is not exalted, nor are my eyes lifted up. Neither have I walked in great things nor in marvels beyond me. If I thought not humbly but exalted my soul, like a weaned child upon its mother” (Psalms 131:1-2).

They also wear linen colobia that barely reach the elbows and, for the rest, leave the hands free. The cutting off of their sleeves is to suggest that they have cut off the deeds and works of this world, and the wearing of linen clothing is to teach them that they have utterly died to a worldly way of life, that thus they may hear the Apostle addressing them daily:

“Put to death your members that are on earth” (Colossians 3:5).

Their very dress proclaims this as well:

“You have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God” (Colossians3:3). And: “I no longer live, but Christ lives in me” (Galatians 2:20).

And:

“The world has been crucified to me and I to the world” (Galatians 6:14).

They wear thin ropes, too, which are braided with a double thickness of wool. . . . They descend from the top of the neck, separate on either side of the neck, go around the folds at the armpits, and are tucked on both sides, so that when they are tightened the garment’s fullness may be gathered close to the body. Thus their arms are freed, and they are unimpeded and ready for any activity as they strive wholeheartedly to fulfill the Apostle’s precept:

“These hands have labored not only for me but also for those who are with me” (Acts 20:34).

“Nor do we eat anyone’s bread for free, but we worked night and day in labor and weariness, lest we burden any of you” (II Thessalonians 3:8).

And:

“If anyone does not wish to work, neither should he eat” (II Thessalonians 3:10).

After this they cover their necks and also their shoulders with a short cape, striving after both modest style and cheapness and economy. In this way, they avoid the cost of coats and cloaks as well as any showiness. These are called “mafortes” in both our language and theirs.

The last pieces of their outfit are a goatskin, which is called a “melotis” or a “pera,” and a staff. These they carry in imitation of those who already in the Old Testament prefigured the thrust of this profession. Of them the Apostle says:

“They went about in melotis and goatskin, needy, in distress, afflicted, the world unworthy of them, wandering in deserts and mountains and caves and caverns of the earth” (Hebrews 11:37-38).

This garment of goatskin signifies that, once all the turbulence of their carnal passions has been put to death, they must abide in the most elevated virtue and no willfulness or wantonness of their youth and of former fickleness must remain in their bodies.

But they refuse shoes as being forbidden by gospel precept (Matthew 10:10), even when bodily infirmity or a winter morning’s chill or the intense midday heat demands them, and they only put sandals on their feet. They understand that this use of them, with the Lord’s permission, means that if, once having been placed in this world, we cannot be utterly removed from the care and worry of this flesh and are unable to be completely rid of it, we should at least provide for the necessities of the body with a minimum of preoccupation and involvement. Thus we should not allow the feet of our soul, which must always be ready for the spiritual race and for preaching the peace of the Gospel . . . to be entangled in the deadly cares of this world — namely, by thinking of what caters not to the needs of nature but to superfluous and harmful pleasure.

This we shall accomplish if, in the words of the Apostle,

“we do not make provision for the flesh in its desires” (Romans 13:14).

But although they legitimately use sandals, since they were conceded by the Lord’s decree, they nonetheless do not allow them on their feet when they approach to celebrate or to receive the most holy mysteries, considering that they must keep literally what was said to Moses and to Joshua the son of Nun:

“Undo the strap of your sandal, for the place on which you stand is holy ground” (Exodus 3:5 and Joshua 5:15).

We have said all of this so that it might not seem that we have left out anything concerning the Egyptians’ garb. But we ourselves should keep only those things that the situation of the place and the custom of the region permit. For the harshness of the winter does not allow us to be satisfied with sandals or colobia or a single tunic, and wearing a little hood and having a “melotis” would evoke derision rather than edification in the beholder. Hence we are of the opinion that, of the things we have mentioned above, we should wear only what is in keeping with the humility of our profession and the character of the climate, so that the whole point of our clothing may not consist in strangeness of apparel, which might be offensive to persons of this world, but in decent simplicity.

More on Monastic Ranks

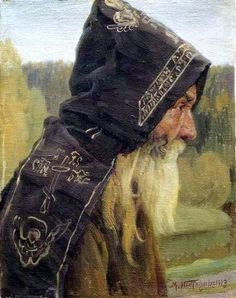

Great Schema (Greek: megaloschemos; Slavonic: Schima)—Monks whose abbots feel they have reached a high level of spiritual excellence reach the final stage, called the Great Schema. The tonsure of a Schemamonk or Schemanun follows the same format as the Stavrophore, and he makes the same vows and is tonsured in the same manner. But in addition to all the garments worn by the Stavrophore, he is given the analavos (Slavonic:analav) which is the article of monastic vesture emblematic of the Great Schema. For this reason, the analavos itself is sometimes itself called the “Great Schema”. It drapes over the shoulders and hangs down in front and in back, with the front portion somewhat longer, and is embroidered with the instruments of the Passion and the Trisagion. The Greek form does not have a hood, the Slavic form has a hood and lappets on the shoulders, so that the garment forms a large cross covering the monk’s shoulders, chest, and back. Another piece added is the Polystavrion (“Many Crosses”), which consists of a cord with a number of small crosses plaited into it. The polystavrion forms a yoke around the monk and serves to hold the analavos in place, and reminds the monastic that he is bound to Christ and that his arms are no longer fit for worldly activities, but that he must labor only for the Kingdom of Heaven. Among the Greeks, the mantle is added at this stage. The paramandyas of the Megaloschemos is larger than that of the Stavrophore, and if he wears the klobuk, it is of a distinctive thimble shape, called a koukoulion, the veil of which is usually embroidered with crosses.

Great Schema (Greek: megaloschemos; Slavonic: Schima)—Monks whose abbots feel they have reached a high level of spiritual excellence reach the final stage, called the Great Schema. The tonsure of a Schemamonk or Schemanun follows the same format as the Stavrophore, and he makes the same vows and is tonsured in the same manner. But in addition to all the garments worn by the Stavrophore, he is given the analavos (Slavonic:analav) which is the article of monastic vesture emblematic of the Great Schema. For this reason, the analavos itself is sometimes itself called the “Great Schema”. It drapes over the shoulders and hangs down in front and in back, with the front portion somewhat longer, and is embroidered with the instruments of the Passion and the Trisagion. The Greek form does not have a hood, the Slavic form has a hood and lappets on the shoulders, so that the garment forms a large cross covering the monk’s shoulders, chest, and back. Another piece added is the Polystavrion (“Many Crosses”), which consists of a cord with a number of small crosses plaited into it. The polystavrion forms a yoke around the monk and serves to hold the analavos in place, and reminds the monastic that he is bound to Christ and that his arms are no longer fit for worldly activities, but that he must labor only for the Kingdom of Heaven. Among the Greeks, the mantle is added at this stage. The paramandyas of the Megaloschemos is larger than that of the Stavrophore, and if he wears the klobuk, it is of a distinctive thimble shape, called a koukoulion, the veil of which is usually embroidered with crosses.

The Schemamonk also shall remain some days in vigil in the church. On the eighth day after Tonsure, there is a special service for the “Removal of the Koukoulion”.

In some monastic traditions the Great Schema is never given or is only given to monks and nuns on their death bed, while in others, e.g., the cenobiticmonasteries on Mount Athos, it is common to tonsure a monastic into the Great Schema only 3 years after commencing the monastic life.

In Russian and some other traditions, when a bearer of some monastic title acquires the Great Schema, his title incorporates the word “schema”. For example, a hieromonk of Great Schema is called hieroschemamonk, archimandrite becomes schema-archimandrite, hegumen – schema-hegumen, etc.