by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

It is important that Christians, when they speak of “human nature,” understand this expression in a biblical sense. And when they are told that “human nature does not change,” they should recognize the assertion as more Aristotelian than Christian. When God created human beings, it was precisely for the purpose of making them something more. Their destiny is not defined by human nature.

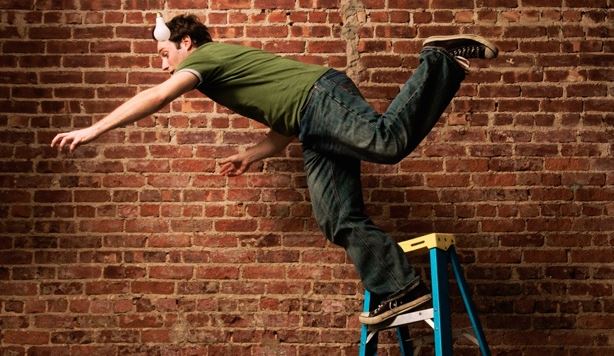

That is to say, it is not of the nature of human beings that their existence is circumscribed within a fixed and predetermined set of expectations. Unlike oak trees and the birds that nest in them, human beings are endowed with freedom of choice. The behavior of plants and animals, inasmuch as their existence is determined by native tropisms and instincts operating within a physical environment, is fairly predictable. Men are called to become something more.

Although it has become common to speak of “natural history,” the noun in this expression is used improperly. History, as this term has been understood ever since Herodotus used it this way, consists in the rational consideration of sequential events. There is no history without rational memory.

In nature—apart from human beings–there are no events. Things happen in nature, but it is not proper to call them events. An earthquake or a solar eclipse, apart from an interpretive regard by human beings, is not an event. When a landslide destroys a tree, the surviving trees do not record its demise, nor do they compose ballads to lament the tragedy. Birds, likewise, if a mighty wind should blow away their nest, do not fabricate new models, designed on better architectural principles. In nature everything remains the same.

Things human, on the other hand—the res humanae—do not remain the same, because human beings make choices. A potential for history is rooted in man’s capacity for free choice.

God gave human beings the gift of free choice—ultimately—for one purpose: so that they could freely choose Him. This purpose, however, does not change freedom into a necessity. Man’s free invitation to theosis (union with God forever) implies the possibility of damnation (the loss of God forever). Free to choose God, man is also able not to choose God.

Thus, the very gift of freedom could become the instrument of man’s Fall. The goodness God put in man, wrote Gregory the Theologian, was not a thing

“sown by nature alone (ou physei monon kataspeiromenon), but as something to be cultivated by our choice (proairesei georgoumenon).”

The

“movements of [man’s] self-determination go in both directions (tois ep’ ampho tou avtexsousiou kinemasin) (Orationes 2.17).”

But God could hardly have left Adam and Eve to figure this out on their own. Their choices required some concrete matter (hyle) on which to be exercised. If they were to choose wisely, they would need instruction, and this was the function of the law, or commandment, that God gave them in the Garden. God was determined, in the very act of creating free human beings, to make sure that they would always know the path to their proper destiny.

Indeed, the concept of freedom includes the imperative of law. At absolutely no point in his history—not even in Eden—has man been deprived of the guidance of “law” (45.28). It is God’s second gift, the necessary supplement to freedom.

How, then, did it happen that man fell? Endowed with a relentless

“quest for God” (28.15),

what prompted him to deviate from the true course of his destiny?

If Gregory had followed the common attempt to find the origins of the Fall in man’s place in the “second stage of Creation” (the world of matter), he would have traced the problem to the physical side of man’s composition. In this he would have shared common ground with Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, Manichaeism, and other dualistic theories prevalent during the golden age of patristic theology.

However, the path to man’s Fall, Gregory believed, did not lie through what was lower in him, but in what was higher. It was in man’s spiritual and noetic nature that he deviated from his destiny. Man’s fall was not occasioned by the world of matter but through the temptation of an apostate angel, the very creature who, in the instance of their creation, most resembled God. Indeed, it was his resemblance to God, his theotes, that enticed Satan to defy God and claim equality with Him (40.10).

And Satan, after his rebellion, enticed human beings, as well, through their own divine vocation, to choose a disobedient and deviant path to their destiny.

“You shall be as gods,”

he promised Adam and Eve. This was the

“deception of the adversary” (klope antikeimenou) (22.13).

Freedom and Man’s Fall