by Maurice A. Robinson

A very strong presumption exists that the exemplars of the earliest genealogically-unrelated minuscule MSS were uncials dating from a much earlier time. These include the minuscules of the ninth and tenth centuries, and likely many within the eleventh century as well. Their exemplars were certainly not any contemporary uncials that only recently had been copied (the destruction of recent exemplars would be economically problematic), but far earlier uncial exemplars dating from the 4th-6th centuries. These would have been sought out for both their general accuracy and antiquity. The disappearance of those uncial exemplars was due to “instant obsolescence” following the transfer into the new minuscule script.

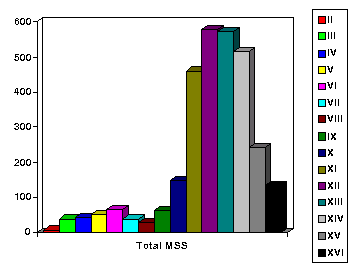

Once copied, the uncial exemplars were apparently disassembled and utilized for scrap and secular purposes, or washed and scraped and reused for palimpsest works both sacred and secular. Such is the proper understanding of the “orphan” status of the early minuscules as stated by Lake, Blake, and New: they did not claim that every exemplar at all times was systematically destroyed after copying, but that, during the conversion period, once a minuscule copy of an uncial exemplar had been prepared, the immediate uncial predecessor was disassembled and reused for other purposes. That this procedure occurred on the grand scale is demonstrated by the dearth of uncial MSS when contrasted to the large quantity of unrelated minuscule MSS as shown in the following chart:

Chart 1: The Extant Continuous-Text MSS in Centuries II-XVI

This is evidenced even during the earliest portion of the minuscule era when both scripts coexisted. The minuscule MSS from the ninth through perhaps the first half of the eleventh century are very likely to represent uncial exemplars far earlier than those uncials which date from the ninth-century. Thus, many early minuscules are likely only two or three generations removed from papyrus ancestors of the fourth century or before, perhaps even closer. There are no indicators opposing such a possibility, and the stemmatically independent nature of most early minuscule witnesses (their “orphan” status as per Lake, Blake, and New) increases the likelihood of such a case. It becomes presumptuous to suppose otherwise, especially when many minuscules are already recognized by modern eclectics to contain “early” texts (defined, of course, by their non-Byzantine nature). As Scrivener noted in 1859,

It has never I think been affirmed by any one … that the mass of cursive documents are corrupt copies of the uncials still extant: the fact has scarcely been suspected in a single instance, and certainly never proved… It is enough that such an [early] origin is possible, to make it at once unreasonable and unjust to shut them out from a “determining voice” (of course jointly with others) on questions of doubtful reading.

It is basically an a priori bias against Byzantine uncials and early minuscules which prevents their recognition as preserving a very early type of text. If such MSS in fact are bearers of ancient tradition, one cannot set an exclusionary date before the mid-eleventh century. Note that the Byzantine-priority theory does not rise or fall upon a late cutoff period; the theory could proceed in much the same form were the end of the sixth century made the cutoff date. However, if a strong presumption exists that (at least) the earliest minuscules preserve a much more ancient text, this could not be done except at risk of eliminating the evidence of many “late” MSS containing texts which are representative of “early” exemplars spanning a broad chronological and geographical range.

The concept of a single “best” MS or small group of MSS is unlikely to have transmissional evidence in its favor. While certain “early” MSS may be considered of superior quality as regards the copying skill of their scribes or the type of text they contain, such does not automatically confer an authoritative status to such MSS. To reiterate: late MSS also contain “early” texts; poorly-copied MSS can contain “good” texts; carefully-copied MSS may contain texts of inferior quality; within various texttypes some MSS will be better representatives than others. But transmissional considerations preclude the concept that any single MS or small group of MSS might hold a status superior either to a texttype or the full conspectus of the stream of transmission. If the Byzantine Textform is considered to be that form of the text from which all other forms derived, it encompasses the remaining component texttype groups. Yet among the MSS which directly comprise the Byzantine Textform, there is no single “best” MS nor any “best group” of MSS; nor can minority Byzantine subgroups override the aggregate integrity of the transmission.

An exclusive following of the oldest MSS or witnesses is transmissionally flawed.The oldest manuscript of all would be the autograph, but such is not extant. Given the exigencies affecting early transmissional history and the limited data preserved from early times, it is a methodological error to assume that “oldest is best.” Since the age of a MS does not necessarily reflect the age of its text, and since later MSS may preserve a text more ancient than that found in older witnesses, the “oldest is best” concept is based on a fallacy. While older MSS, versions, and fathers demonstrate a terminus a quo for a given reading, their respective dates do not confer authenticity; they only establish the existence of a given reading at a given date. All readings within a variant unit should be considered under all aspects of transmission: minority readings which leave no continual trace throughout transmissional history are suspect; they are not made more authentic merely by an appearance in one or a few ancient witnesses.

Transmissional considerations coupled with internal principles point to the Byzantine Textform as a leading force in the history of transmission. The Byzantine Textform is not postulated a priori to be the original form of the text, nor even the superior texttype. The conclusion follows only as a logical deduction from internal and external considerations viewed from a transmissional-historical framework. Note particularly that there is no automatic probability that the majority of witnesses will overwhelm the MS tradition at any particular point–this despite transmissional expectations.

Many variant units show the mass of Byzantine-era MSS divided nearly evenly among two or more competing readings. This serves as clear evidence that there can be no automatic anticipation of either textual uniformity or overwhelming numerical support among the MSS comprising the Byzantine Textform. When a relative uniformity does occur beyond the equally-divided cases, this indicates a transmissional transcendence of probabilities, and serves as presumptive evidence in favor of those readings which find strong transmissional support as a result of unplanned consequence. Rather than a cause for suspicion or rejection, those places where the MSS of the Byzantine Textform stand nearly uniform argue strongly for transmissional originality, based upon the evidence of the divided cases.

Once the Byzantine Textform gains validity on the basis of the preceding considerations, it can be granted a significant voice regarding the establishment of the original text. The result flows naturally from transmissional considerations, but is not dictated by presuppositions external to transmissional factors. Indeed, were any other texttype to demonstrate the same transmissional criteria, that texttype would be favored over the Byzantine.

Note that the Byzantine-priority hypothesis can do nothing to resolve the many cases where external evidence is divided and where no reading clearly dominates. In such cases, internal principles coupled with transmissional probabilities must be invoked to determine the strongest reading. Similarly, in many cases internal principles offer no clear decision, and external canons must take a leading role. Cases also exist where the MSS are divided and where internal evidence is not determinative, in which a reasonable scholarly estimate is the best one can expect.

The primary rules for balancing internal and external evidence are simple, and are ordered in accordance with known facts regarding scribal habits:

(1) one should evaluate readings with the intention of discovering antecedent transcriptional causes;

(2) readings should be considered in the light of possible intentional alteration;

(3) finally, readings within a variant unit must be evaluated from a transmissional-historical perspective to confirm or modify preliminary assessments.

The rigorous application of this methodology will lead to valid conclusions established on a sound transmissional basis. Such accords with what we are told by known scribal habits and the extant manuscript evidence considered in light of transmissional process.

Part Eight will be published on July 19th.

This excellent article is reprinted with permission of TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism .

© TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism, 2001.