by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

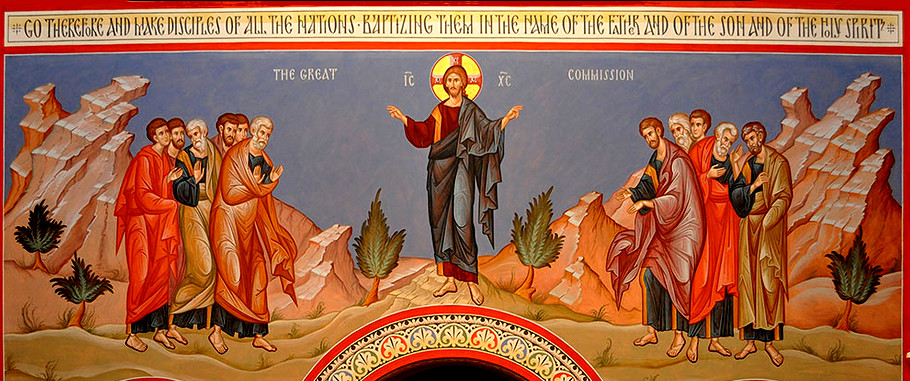

It is instructive to compare and contrast the closing scenes of Jesus’ earthly presence as they are presented in Luke/Acts and Matthew. The scenes are similar in that both depict Jesus’ final meeting with the group known as the Eleven (hoi Hendeka, Mt 28:16 and Lk 24:33). Connected with each presentation, likewise, is an evangelical mandate (Mt 28:19-20 ; Lk 24:46-47 ; Acts 1:8). In both cases the Eleven prostrate themselves before Jesus (prokyneo, Matthew 28:17 and Luke 24:52).

Another similarity is that both scenes take place on a hill.

These similarities, however, serve chiefly to highlight the differences between the two presentations. For example, the “hill” (oros) in Matthew 28:16 is found in Galilee, whereas Luke’s hill is, by implication, the Mount of Olives, just east of Jerusalem (24:50).

The major difference between the two stories, however, has to do with what happens to the Lord. According to Luke, he takes leave of the Church and ascends into heaven, whereas in Matthew’s account he does not take leave of the Church. He declares, on the contrary,

“Behold, I am with you all days, even till the end of the world.”

There is not one word about his ascending. According to Luke Jesus departs; according to Matthew he stays. Which is it, then? Did Jesus leave this earth or did he remain here?

The later editor of Mark’s Gospel apparently sensed the point of this question. According to the final scene he added to the Markan account, the risen Lord both goes and stays:

“So then, after the Lord had spoken to them, he was received up into heaven, and sat down at the right hand of God. And they went out and preached everywhere, the Lord working with them and confirming the word through the accompanying signs (Mark 16:19-20; emphasis added).

One grasps the point made here if he reflects that this text twice calls Jesus “the Lord.” because his lordship is manifest in two ways: by his Ascension into glory and through his continued presence in the ministry of the Church.

Both aspects of Jesus’ lordship-in heaven and on earth-are conveyed in the opening lines of Psalm 109 (110):

“The Lord said to my Lord, / ‘Sit as My right hand, / until I make your enemies the footstool of your feet.’ / The Lord will send the rod of your power out of Zion. Rule in the midst of your enemies.”

In the first assertion of this psalm, Jesus is enthroned in heaven, seated at the right hand of the Father. The next lines, however, speak of his “power” (dynamis) going forth from Zion, that is, Jerusalem.

This dual exercise of Jesus’ lordship is precisely what we find in the New Testament, where the Apostles, after they witness the Ascension, receive “power” (dynamis) when the Holy Spirit comes upon them (Acts 1:8).

The Church Fathers believed this to be the correct sense of the opening lines of Psalm 109. Justin Martyr, for example, explained the psalm this way in the mid-second century:

“And that God the Father of all would bring Christ up to heaven after He had raised him from the dead, and would keep him there until He subdues his demonic enemies, and until the number of those who are foreknown by Him as good and virtuous, is complete. . . . Hear what was said by the prophet David. These are his words: ‘The Lord said unto my Lord, Sit at My right hand, until I make your enemies your footstool. The Lord will send to you the rod of power (hrabdon dynameos) out of Jerusalem; and rule in the midst of your enemies.’ . . . That which he says, ‘He shall send the rod of power out of Jerusalem,’ was a prophecy of the mighty word, which his apostles, going forth from Jerusalem, preached everywhere” (Apology 45).

Justin perceives two icons of lordship in this psalm: The first is Jesus’ session at the right hand of the Father in heaven; the second is the extension of his scepter, his “rod of power,” in this world. In both places—triumphant in heaven and militant in this world—Jesus is Lord.

The reign of Christ in heaven is not separable from the evangelical mission of the Church on earth. St. Peter, in his first sermon, established the union of these two ideas, citing the opening lines of Psalm 109 as the basis of the Church’s message and summons to repentance:

“This Jesus God raised up, of whom we are all witnesses. Therefore being exalted to the right hand of God, and having received from the Father the promise of the Holy Spirit, he poured out what you now see and hear. For David did not ascend into the heavens, but he, himself, says: ‘The Lord said to my Lord, / ‘Sit at My right hand, / Till I make Your enemies Your footstool.’ Therefore let all the house of Israel know assuredly that God has made this Jesus, whom you crucified, both Lord and Christ. . . . Repent, and let every one of you be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ for the remission of sins; and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit” (Acts 2:33-39).