Susannah the Heroine

Part Two describes the – dare I say- hesychastic quality of Susannah’s prayer and virtue, the patristic witness of her struggle, and the parallels between her and Joseph of Egypt. Truly, a great heroine of the Old Testament, and a model for all Christians.

by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

Susannah, whose name was traditionally understood to mean “lily,” has ever been held in the highest regard by Christians. Jerome called her the woman

Susannah, whose name was traditionally understood to mean “lily,” has ever been held in the highest regard by Christians. Jerome called her the woman

“noble in faith,”

and she was described by Chromatius of Aquileia as

“that most noble woman.”

Her chief adornments, said Hippolytus, were

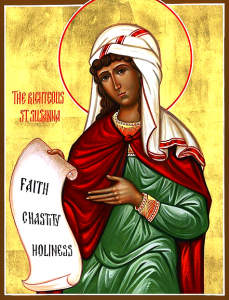

“faith, chastity, and holiness.”

Faithful to the vows of her marriage, she would be repeatedly held up by Ambrose and others as a sterling model of married chastity.

Indeed, said Zeno of Verona, Susan-nah valued her chastity more than her life. She feared disgrace more than death; truly, the only death she feared was the death of the soul by sin, said Jerome. Theodoret of Cyr exalted her as one who chose wisely and bravely with a safe conscience.

“In the sense of the Gospel,” wrote Hippolytus, “Susannah despised those who can kill the body, in order that she might save her soul from death.”

Thus, Stephen of Grandmont observed that God, in saving Susannah from sinning, showed her an even greater mercy than in saving her from death.

Christians have been particularly impressed that Susannah, when falsely accused, spoke not a word to defend herself. Moreover, in Theodotion’s version, which differs in this respect from the Septuagint, she did not even raise her voice in prayer until after her condemnation. Rather, she prayed silently during her accusation and trial. As she was being accused, the text says, she simply

“looked up with tears to heaven, because her heart trusted in the Lord.”

“By her tears,” wrote Hippolytus, “she drew the Word from heaven, who himself was with tears able to raise the dead Lazarus.”

As Origen observed, this devout gesture of Susannah is graced with a great literary irony, for it is to be contrasted with the description of her two lustful accusers:

“Thus they perverted their own minds and turned away their eyes from looking up to heaven, and they rendered not just judgments.”

So Susannah, said Ambrose, did not attempt to justify herself, but sought in prayer the justice of God. The Church Fathers never ceased to praise Susannah’s silent prayer. The Lord heard her petition, wrote Hippolytus, because

“God hears those who call upon Him from a pure heart.”

According to Ambrose,

“She kept silence and conquered.”

And again:

“Susannah bent her knee to pray and triumphed over the adulterers”;

“keeping silence among men, she spoke to God.”

And Augustine:

“She kept silence and cried out with her heart”;

“Her mouth closed, her lips unmoved, Susannah cried out with this voice.”

And Jerome:

“Great was this voice, not by the movement of the air nor the cry from the jaws, but by the greatness of her modesty, through which she cried out to the Lord.”

And again:

“The affection of the heart, and the pure confession of the mind, and the good of her conscience rendered her voice the clearer, so great was her shout to God that was not heard by men.”

There were similar observations by Maximus the Confessor and others.

We may summarize the traditional treatment of this aspect of the story by quoting Leander of Seville, who speaks of the most virtuous Susannah, who did not reply with words of justice to those who accused her of adultery, although she had that justice in her heart; nor did she repel the adulterers by any claims of her own, but with a pure conscience she entrusted herself to God alone with sighs and groans, for He is the One who sees within our minds; and thus she who did not wish to be defended by her own words was defended by the divine judgment, so that God was witness for her of the guiltless conscience that she bore and as she was being led to punishment, revealed the fact of her innocence.

We may summarize the traditional treatment of this aspect of the story by quoting Leander of Seville, who speaks of the most virtuous Susannah, who did not reply with words of justice to those who accused her of adultery, although she had that justice in her heart; nor did she repel the adulterers by any claims of her own, but with a pure conscience she entrusted herself to God alone with sighs and groans, for He is the One who sees within our minds; and thus she who did not wish to be defended by her own words was defended by the divine judgment, so that God was witness for her of the guiltless conscience that she bore and as she was being led to punishment, revealed the fact of her innocence.

Nor is it without interest that Susannah’s temptation took place in a garden (paradeiso). Indeed, unlike the Septuagint, Theodotion’s version also places the entire trial in that same location, the “scene of the crime.” As the place of Susannah’s temptation, false accusation, and final vindication, therefore, this Danielic “paradise,” said Hippolytus, is to be contrasted with the garden of Genesis 3, where Eve was tempted, justly accused, and finally banished:

“As formerly the devil was disguised in the serpent in the garden, so now is he concealed in the two elders, whom he arouses with his own lust, that he might once again seduce Eve.”

The Book of Daniel abounds, of course, with cases of accusations against God’s servants, followed by their divine deliverance, and in this respect the account of Susannah certainly fits the pattern. Jerome especially drew attention to her resemblance to the three youths condemned to the furnace. In the Catacomb of St. Priscilla in Rome, Susannah appears near a picture of Daniel in the lions’ den.

Of all the characters in Holy Scripture, however, it was inevitable that Susannah would most be compared to Joseph, in the case of Potiphar’s wife. Indeed, the resemblance between the two instances is remarkable:

- Joseph and Susannah both resistant to assaults against their chastity,

- both falsely accused by those who lusted after them,

- both maintaining silence when accused, both condemned in a foreign country, and

- both finally vindicated by a providential intervention.

No wonder that Christian readers (Origen, Athanasius, Didymus, Ambrose, and others) repeatedly elaborated comparisons between the two of them, whether in respect to their chastity under severe trial, to their being falsely indicted and condemned by their tempters, or to their patient silence when accused.