by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon

In all four Gospels, the standard format is the “incident.” They have an episodic structure; each Gospel is a series of what the Greeks called the epeisodos or epeisodion.

In all four Gospels, the standard format is the “incident.” They have an episodic structure; each Gospel is a series of what the Greeks called the epeisodos or epeisodion.

The Gospels are made up of short stories; although each gospel is an integral literary composition, anyone can see that they were intended to be read story-by-story. These small narratives go by the Greek name pericope, which means “a rounded section.” Obviously, the established lectionaries present the Gospels this way.

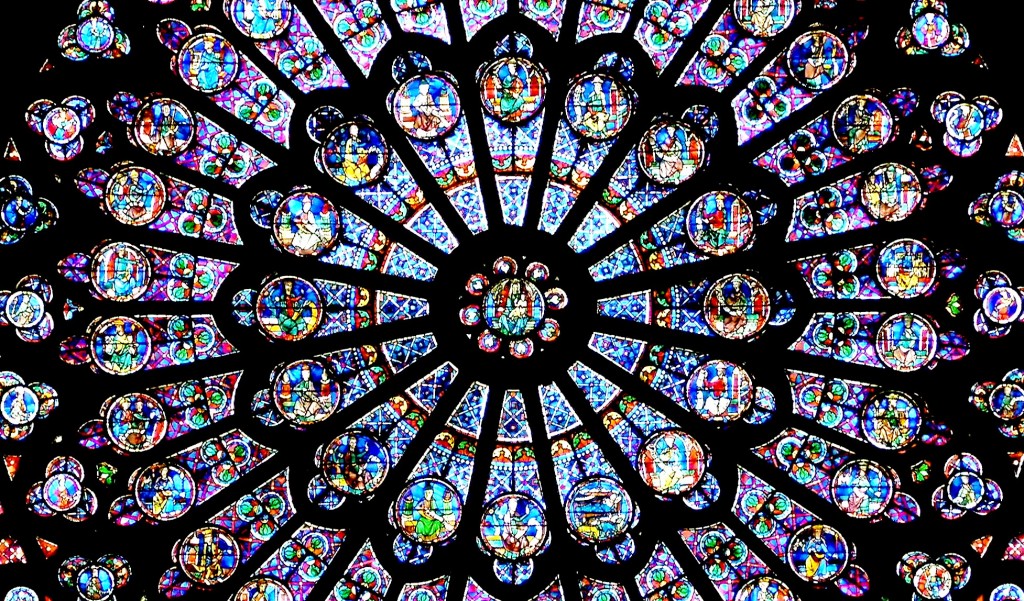

Christians assimilate the mystery of Redemption in bite-size portions. The life, ministry, and teaching of Jesus are mediated to the Church in reasonably enclosed frames of narrative. Each account represents a window, as it were, through which believers contemplate the apologos katholikos, the story as a whole.

Indeed, the impression of a door into a larger setting is conveyed in the Greek word itself; an epeisodion is literally an “entrance besides.” An episode gives access to a vista larger than itself.

Let me suggest that the episodic quality of the Gospels prompts a comparison with both framed art and the stage. Indeed, I submit that all these forms take their rise from the same impulse: the need for a concentrated regard of the part in order to contemplate the whole. Chesterton perceived this need when he remarked on

“the boundary line that brings one thing sharply against another.”

He went on to explain,

“All my life I have loved frames and limits; and I will maintain that the largest wilderness looks larger seen through a window.”

A framed gaze at reality—whether in a window, or in the theater, or in panel art, or in episodic narrative—enjoys a two-fold advantage:

First, recognizing that limitation is necessary to form, it draws contemplation to a focus. Whether in a scene of Macbeth or a seascape of Turner, one receives the whole truth in a size not too big to ingest.

Second, the restraining lines of a frame or a window indicate a proper humility in the presentation. The framework announces, even before the story begins, that the composition strives to be no more than an outline. Perhaps the German equivalent, Grundriss, better insinuates what I have in mind here: both the foundational aspect of the enterprise and the humility in which it is grounded.

The Gospel itself declares the benefit of this narrative humility:

“Whoever humbles himself will be exalted.”

In a framed presentation the myriad elements left unspoken form an internal and luminous exaltation, an intimation of the unused energy of truth. The cataphatic components of a scene implicitly convey the unseen glory.

The limitations imposed by a narrative, theatrical, or artistic frame are not negative but positive. Sometimes one sees more by seeing less. For instance, neither in life nor on canvas does a viewer gaze straight at the sun. Indeed, a direct attention to the sun effectively precludes the sight of anything else—forever. The sun’s exaltation is discerned, rather, in the humbler contrast of lights and shadows. The wind, too, abases itself on the canvas; its exaltation is conveyed in the bent branches and the turbulence of the wave. Art of any kind humbles itself in order to be exalted.

In the theater, the energy and “exaltation” of a given scene come largely from off-stage, being derived from the discerned plot and context of the whole story. Indeed, few theatrical scenes are intelligible except within an “act” and the entire production. Plot and assumed context provide the sun and wind, as it were, of the narrative portrayed in the immediate scene.

We may further reflect that windows are usually quadrangular. Quadrangles are far more stable-and, therefore, dependable-than circles, inasmuch as circles have a tendency to roll away. The quadrangle, by holding everything steady, favors analysis. Angles encourage discourse. The viewer—or reader—is disposed to trace lines and pose questions, whether to panels, windows, or pages.

The viewer is inspired to come at the subject from dialectically contrasted points, where progressing lines dramatically change direction and “bend back.” Angles—literally—reflect. This is important; no one appreciates a story or scene that just runs around in circles.

A similar angularity contours the stories in the Gospels—a feature, I suggest, favoring critical reflection on their content. Taut lines are drawn between angled points. Sundry tensions are strung from contrasting corners of the story. The stress of oppositions is everywhere: Jesus and his enemies, a rich man and Lazarus, deformity and healing, stormy waves and a calm sea, Mary and Martha, before and after, life and death, heaven and hell,

“You have heard it said” and “but I say unto you,”

and so on.

The concentrated energy in each scene discloses the drama of the whole story.

Every scene in the Gospels, whatever its length, is set within humbling limits that confer both form and freedom; nothing in the narrative is allowed to fly out into space. Each component in the presentation holds its place.

Recall, for instance, the four friends suspending the paralytic from the penetrated roof into the presence of Jesus, the equally penetrating gaze Jesus fixes upon them, his unexpected declaration to the suspended man, the silent hostility and damning accusation of his enemies, and Jesus’ apodictic reply. The sundry narrative tensions in the scene are represented by the gravitational pull that holds taut the angled ropes attached to the paralytic’s pallet.

One finds something of this pattern in virtually every story in the Gospels.